Say what you want about the current crop of mass-marketed consumer-grade cordless tools, but they’ve got one thing going for them — they’re cheap. Cheap enough, in fact, that they offer a lot of hacking opportunities, like this portable bench power supply that rides atop a Ryobi battery.

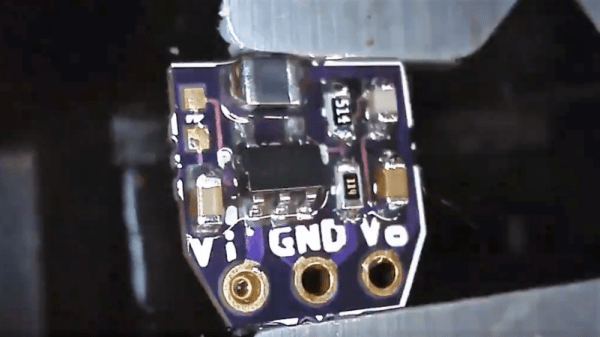

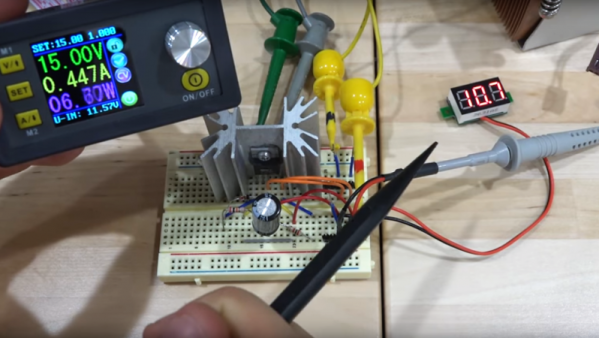

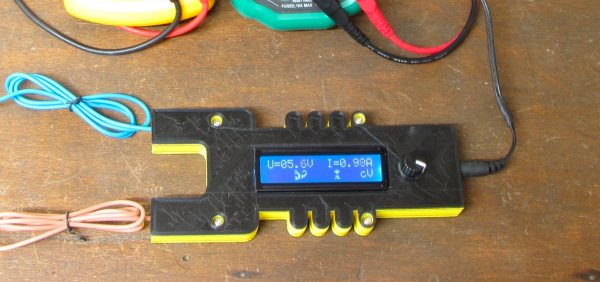

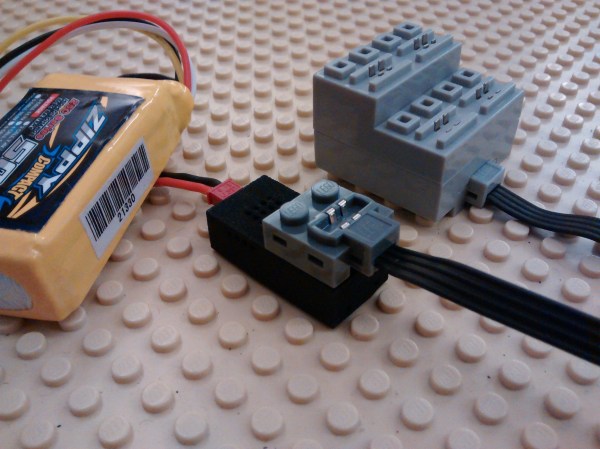

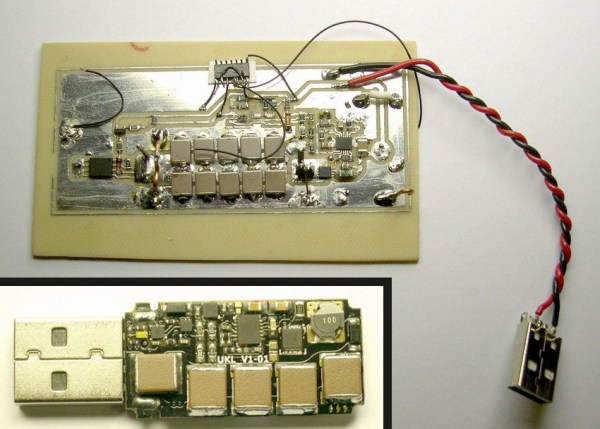

Like many of the more common bench supply builds we’ve seen, [Pat K]’s more portable project relies on the ubiquitous DPS5005 power supply module, obtained from the usual sources. [Pat K] doesn’t get into specifics on performance, but supplied with 18 volts from a Ryobi One+ battery, the DC-DC programmable module should be able to do up to about 16 volts. Mating the battery to the supply is easy with the 3D-printed case, which has a socket for the battery that mimics the sockets on tools from the Ryobi line. It’s simple and effective, as well as neatly executed. The files for the case are on Thingiverse; sadly, only an STL file is included, so if you want to support another brand’s batteries, you’ll have to roll your own.

Check out some of the other power supplies we’ve featured that use the DPS5005 and its cousins, like this nice bench unit. We’ve also covered some of the more hackable aspects of this module, such as an open-source firmware replacement.