Although humanity was hoping for a more optimistic robotic future in the post-war era, with media reflecting that sentiment like The Jetsons or Lost in Space, we seem to have shifted our collective consciousness (for good reasons) to a more Black Mirror/Terminator future as real-world companies like Boston Dynamics are actually building these styles of machines instead of helpful Rosies. But this future isn’t guaranteed, and a PhD researcher is hoping to claim back a more hopeful outlook with a robot called Blossom which is specifically built to investigate how humans interact with robots.

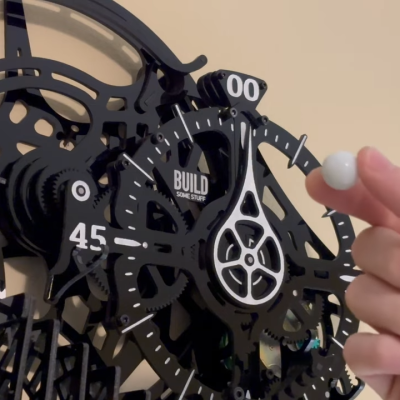

For a platform this robot is not too complex, consisting of an accessible frame that can be laser-cut from wood with only a few moving parts controlled by servos. The robot is not too large, either, and can be set on a desk to be used as a telepresence robot. But Blossom’s creator [Michael] wanted this to help understand how humans interact with robots so the latest version is outfitted not only with a large language model with text-to-speech capabilities, but also with a compelling backstory, lore, and a voice derived from Animal Crossing that’s neither human nor recognizable synthetic robot, all in an effort to make the device more approachable.

To that end, [Michael] set the robot up at a Maker Faire to see what sorts of interactions Blossom would have with passers by, and while most were interested in the web-based control system for the robot a few others came by and had conversations with it. It’s certainly an interesting project and reminds us a bit of this other piece of research from MIT that looked at how humans and robots can work productively alongside one another.

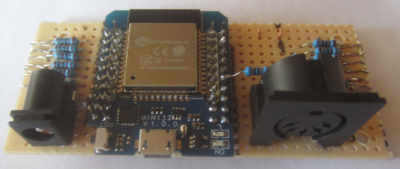

settled upon a simple linear arrangement of beams held within a laser-cut wooden box frame. Since these laser modules are quite small, some aluminium rod was machined to make some simple housings to push them into, making them easier to mount in the frame and keeping them nicely aligned with their corresponding LDR.

settled upon a simple linear arrangement of beams held within a laser-cut wooden box frame. Since these laser modules are quite small, some aluminium rod was machined to make some simple housings to push them into, making them easier to mount in the frame and keeping them nicely aligned with their corresponding LDR.