It’s the suburbanista’s weekend nightmare: you’re almost done with the weekly chores, taking the last few passes with the lawn mower, when you hear a pop and bang. The cylinder head on your mower just blew, and you’re out of commission. Or are you? You’ve got a 3D printer – couldn’t it save the day?

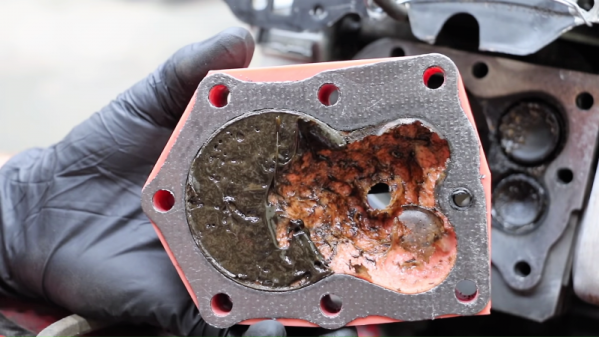

If this bench test of plastic cylinder heads is any indication, it’s possible – just as long as you’ve only got 40 seconds of mowing left to do. [Project Farm] has been running all sorts of tests on different materials as field-expedient cylinder heads for small gasoline engines, using everything from JB Weld epoxy to a slab of walnut. For this test, two chunky heads were printed, one from ABS, of the thermochromic variety apparently, the other in PLA. The test went pretty much as expected for something made of thermoplastic exposed to burning gasoline at high pressure, although ABS was the clear winner with two 40-second runs. The PLA only lasted half as long before the spark plug threads melted and the plug blew out. A gasket printed from flexible filament was also tested, with predictably awful results.

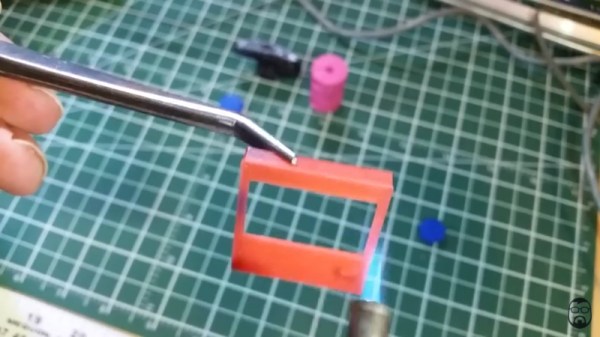

As bad as all this was, it still shows that 3D-printed parts are surprisingly tough. Each part was able to perform decently under a compression test, showing that they can stand up to pressure as long as there’s no heat. If nothing else, it was a learning experience. And as an aside, the cylinder heads were printed by [Terry] from the RedNeckCanadians YouTube channel. That video is worth a watch, if just for a few tips on making a 3D-printed copy of an object. Continue reading “Results Of 3D-Printed Cylinder Head Testing Fail To Surprise”