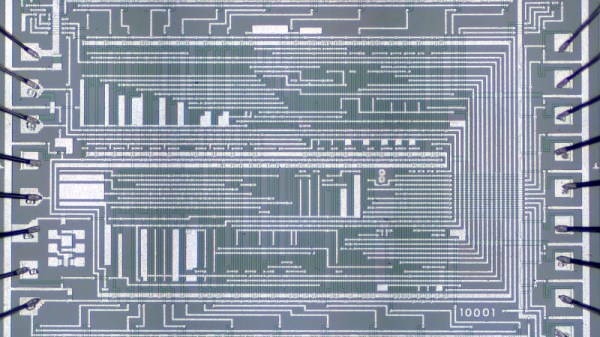

We’ve seen so many explorations of older semiconductors at the hands of [Ken Shirriff], that we know enough to expect a good read when he releases a new one. His latest doesn’t disappoint, as he delves into the workings of one of the first hand-held electronic calculators. The Sharp EL-8 from 1969 had five MOS ICs at its heart, and among them the NRD2256 keyboard/display chip is getting the [Shirriff] treatment with a decapping and thorough reverse engineering.

The basic functions of the chip are explained more easily than might be expected since this is a relatively simple device by later standards. The fascinating part of the dissection comes in the explanation of the technology, first in introducing the reader to PMOS FETs which required a relatively high negative voltage to operate, and then in explaining its use of four-phase logic. We’re used to static logic that holds a state depending upon its inputs, but the technologies of the day all called for an output transistor that would pull unacceptable current for a calculator. Four phase logic solved this by creating dynamic gates using a four-phase clock signal, relying on the an output capacitor in the gate to hold the value. It’s a technology that lose out in the 1970s as later TTL and CMOS variants arrived that did not have the output current drain. Fascinating stuff!

[Ken] gave a talk at the Hackaday Superconference a couple of years ago, if you’ve not seen it then it’s worth a watch.