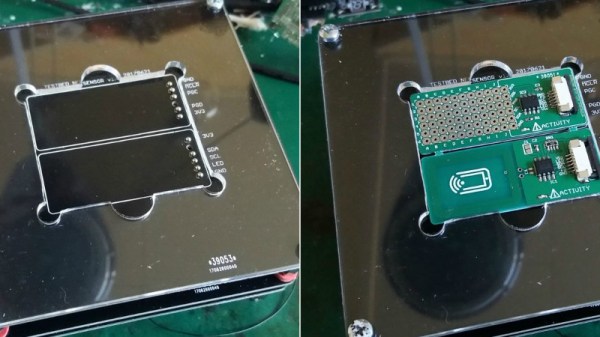

In the past, [Sjaak] has had his testing and programming jigs made for him in Shenzhen, but realized they weren’t that great of a value. They weren’t terribly expensive in the grand scheme of things, but they didn’t include any wiring, so he was still spending his own time and money. His quest to develop his own in-house jigs not only netted him a considerable cost savings in the end, but also produced a nicely detailed post on his site for anyone else who may be heading down the same path. That’s a win-win in our book.

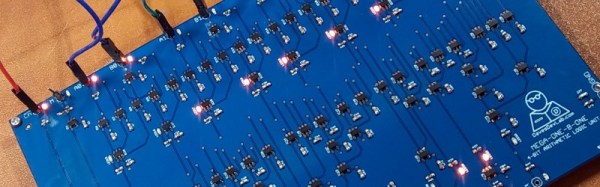

The idea behind a jig is pretty simple: essentially it’s just a mount that holds the PCB, and a set of pins which contact the appropriate points on the board. The jig can then provide power, programming, status LEDs for testing, etc. Basically anything that you can’t or don’t want to include on the final board, but will help in testing or programming them.

The idea behind a jig is pretty simple: essentially it’s just a mount that holds the PCB, and a set of pins which contact the appropriate points on the board. The jig can then provide power, programming, status LEDs for testing, etc. Basically anything that you can’t or don’t want to include on the final board, but will help in testing or programming them.

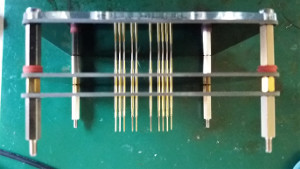

To start, [Sjaak] begins with a blank PCB in Eagle and imports his target board. With the two lined up, he can then mark where he wants the pins to go on the jig, and add labels to the silkscreen to make things a little easier during diagnostics. The target board is then removed, the file converted to Gerber, and it’s sent off for manufacturing. With a few more tweaks, the file is then exported to DXF and laser cut out of acrylic. When the PCBs come back, it’s just a matter of sandwiching it all together with some standoffs and adding the pins.

[Sjaak] mentions that he was inspired by an old post on how SparkFun was internally handling their test jigs, though we think with a dash of automation he could make things even easier for himself.

The highlights of the NeuroBytes Kickstarter include seven different types of neurons for different sensory systems, kits to test the patellar reflex, and what is probably most interesting to the Hackaday crowd, a Braitenberg Vehicle chassis, meant to test the ideas set forth in Valentino Braitenberg’s book, Vehicles: Experiments in Synthetic Psychology. If that book doesn’t sound familiar, BEAM robots probably do; that’s where the idea for BEAM robots came from.

The highlights of the NeuroBytes Kickstarter include seven different types of neurons for different sensory systems, kits to test the patellar reflex, and what is probably most interesting to the Hackaday crowd, a Braitenberg Vehicle chassis, meant to test the ideas set forth in Valentino Braitenberg’s book, Vehicles: Experiments in Synthetic Psychology. If that book doesn’t sound familiar, BEAM robots probably do; that’s where the idea for BEAM robots came from.