What do you do, when you need a random number in your programming? The chances are that you reach for your environment’s function to do the job, usually something like rand() or similar. This returns the required number, and you go happily on your way.

number generator. [by KCAuXy4p CC0 1.0]

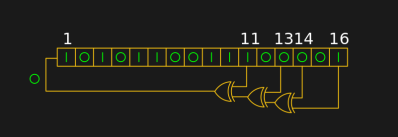

There is a handy way to deal with the PRNG predictability problem, and it lies in ensuring that its random number generation starts at a random point. Imagine the shift register in the previous paragraph being initialised with a random number rather than a string of zeros. This random point is referred to as the seed, and if a PRNG algorithm can be started with a seed derived from a truly unpredictable source, then its output becomes no longer predictable.

Selecting Unpredictable Seeds

Computer systems that use a PRNG will therefore often have some form of seed() function alongside their rand() function. Sometimes this will take a number as an argument allowing the user to provide their own random number, at other times they will take a random number from some source of their own. The Sinclair 8-bit home computers for example took their seed from a count of the number of TV frames since switch-on.

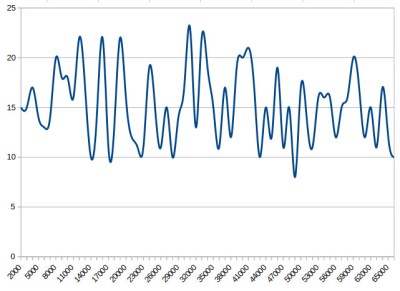

The Arduino Uno has a random() function that returns a random number from a PRNG, and as you might expect it also has a randomSeed() function to ensure that the PRNG is seeded with something that will underpin its randomness. All well and good, you might think, but sadly the Atmel processor on which it depends has no hardware entropy source from which to derive that seed. The user is left to search for a random number of their own, and sadly as we were alerted by a Twitter conversation between @scanlime and @cybergibbons, this is the point at which matters start to go awry. The documentation for randomSeed() suggests reading the random noise on an unused pin via analogRead(), and using that figure does not return anything like the required level of entropy. A very quick test using the Arduino Graph example yields a stream of readings from a pin, and aggregating several thousand of them into a spreadsheet shows an extremely narrow distribution. Clearly a better source is called for.

Noisy Hardware or a Jittery Clock

As a slightly old-school electronic engineer, my thoughts turn straight to a piece of hardware. Source a nice and noisy germanium diode, give it a couple of op-amps to amplify and filter the noise before feeding it to that Arduino pin. Maybe you were thinking about radioactive decay and Geiger counters at that point, or even bouncing balls. Unfortunately though, even if they scratch the urge to make an interesting piece of engineering, these pieces of hardware run the risk of becoming overcomplex and perhaps a bit messy.

The best of the suggestions in the Twitter thread brings us to the Arduino Entropy Library, which uses jitter in the microcontroller clock to generate truly random numbers that can be used as seeds. Lifting code from the library’s random number example gave us a continuous stream of numbers, and taking a thousand of them for the same spreadsheet treatment shows a much more even distribution. The library performs as it should, though it should be noted that it’s not a particularly fast way to generate a random number.

So should you ever need a truly random number in your Arduino sketch rather than one that appears random enough for some purposes, you now know that you can safely disregard the documentation for a random seed and use the entropy library instead. Of course this comes at the expense of adding an extra library to the overhead of your sketch, but if space is at a premium you still have the option of some form of hardware noise generator. Meanwhile perhaps it is time for the Arduino folks to re-appraise their documentation.

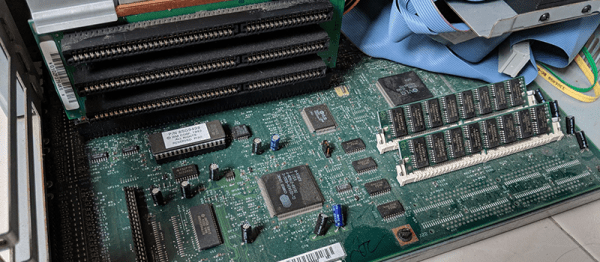

The subject of entropy and generating random numbers is one that has appeared on these pages many times. [Voja Antonic] made a in-depth study using uninitialized RAM as an entropy source for microcontrollers. If you have an insatiable appetite for understanding Linux entropy, we point you at [Elliot Williams]’ comprehensive examination of the subject.

[Arduino image: DustyDingo Public domain]