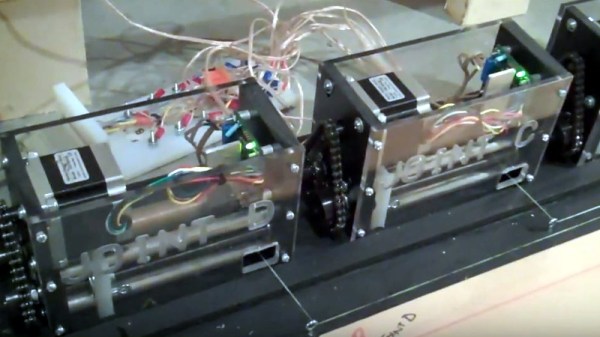

Some hackers have a style all their own that is immediately recognizable from one project to the next. For instance, you can tell a [Takashi Kaburagi] by its insides. The behavior of his Farting Baseball project (machine translation) is amusing, but the joke is only skin deep. Look inside and you’ll gain a huge appreciation for what has been done here. It’s not as mind-boggling as his work on the self-solving Rubiks cube robot, but the creativity and design constraints are similarly impressive.

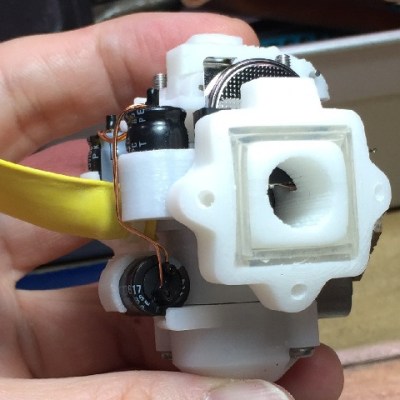

This whimsical project is a curve ball no matter who throws it. While in flight, a jet of compressed gas can alter the trajectory at the press of a button. Inside is a small pressure vessel that is filled with HFC134A refrigerant commonly used on gas blowback pistols. It’s a non-combustible that lies in wait until a solenoid is activated to release the pressure in a powerful jet. The ball carries a CR2032 to power the wireless link for activation, but that solenoid needs more juice so capacitors are charged for this purpose.

It’s worth digging through the details on this one, including the article on measuring discharge time (machine translation). There are numerous nice touches, like the yellow Whoopee Cushion neck that directs the jet, the capacitor discharge materials so there is not an accidental activation when not in use, and clever and clean construction that make everything fit.

Another hacker with an equally iconic style is [Mohit Bhoite]’s work; make his flywire sculptures your next stop.

Continue reading “Farting Baseball; From The Makers Of Self-Solving Rubik’s Cube”