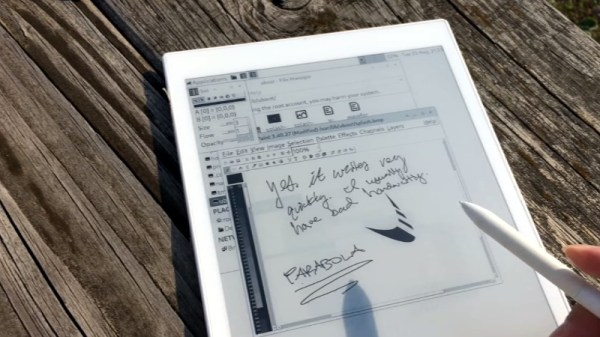

If you’re looking to rid your day to day life of dead trees, there’s a good chance you’ve already heard of the reMarkable tablet. The sleek device aims to replace the traditional notebook. To that end, remarkable was designed to mimic the feeling of writing on actual paper as closely as possible. But like so many modern gadgets, it’s unfortunately encumbered by proprietary code with a dash of vendor lock-in. Or at least, it was.

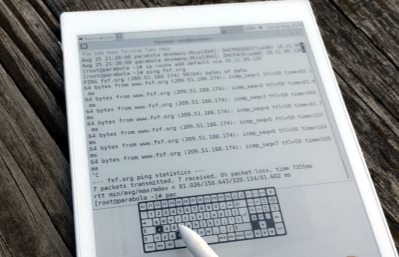

[Davis Remmel] has been hard at work porting Parabola, a completely free and open source GNU/Linux distribution, to the reMarkable. Developers will appreciate the opportunity to audit and modify the OS, but even from an end-user perspective, Parabola greatly opens up what you can do on the device. Before you were limited to a tablet UI and a select number of applications, but with this replacement OS installed, you’ll have a full-blown Linux desktop to play with.

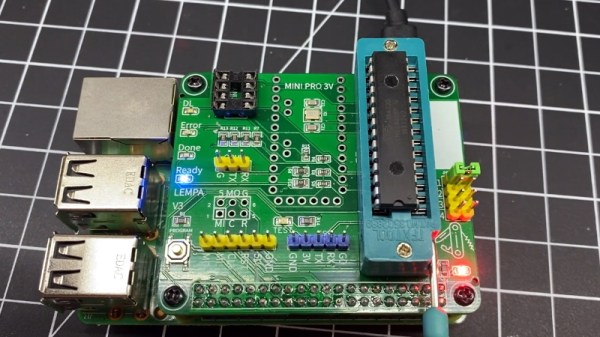

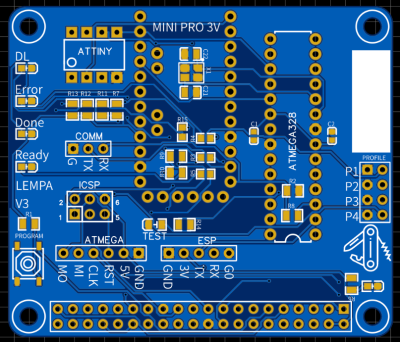

You still won’t be watching videos or gaming on the reMarkable (though technically, you would be able to), but you could certainly use it to read and edit documents the original OS didn’t support. You could even use it for light software development. Since USB serial adapters are supported, microcontroller work isn’t out of the question either. All while reaping the considerable benefits of electronic paper.

You still won’t be watching videos or gaming on the reMarkable (though technically, you would be able to), but you could certainly use it to read and edit documents the original OS didn’t support. You could even use it for light software development. Since USB serial adapters are supported, microcontroller work isn’t out of the question either. All while reaping the considerable benefits of electronic paper.

The only downside is that the WiFi hardware is not currently supported as it requires proprietary firmware to operate. No word on whether or not [Davis] is willing to make some concession there for users who aren’t quite so strict about their software freedoms.

We’ve been waiting patiently for the electronic paper revolution to do more than replace paperbacks with Kindles, and devices like the reMarkable seem to be finally moving us in the right direction. Thankfully, projects that aim to bring free and open source software to these devices mean we won’t necessarily have to let Big Brother snoop through our files in the process.