Waveshare, known for e-ink components aimed at hobbyists among other cool parts, has recently released a very interesting addition to their product line. This is an enclosed e-ink display which gets updated over a wireless NFC connection. By that description, nothing head-turning, but the kicker is that there is no battery inside the device at all, as it harvests the energy needed from the wireless communication itself.

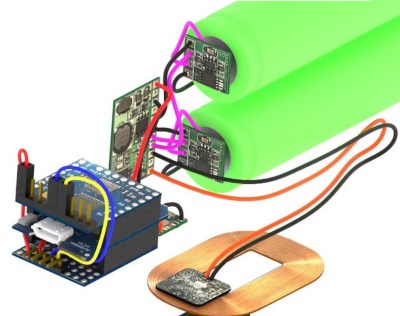

Just like wireless induction charging in certain smartphones, the communication waves involved in NFC can generate a small current when passing through a coil, located on this device’s PCB. Since microcontrollers and e-ink displays consume a very small amount of current compared to other components such as a backlit LCD or OLED display, this harvested passive energy is enough to allow the display to update. And because e-paper requires no power at all to retain its image, once the connection is ended, no further battery backup is needed.

The innovation here doesn’t come from Waveshare however, as in 2013 Intel had already demoed a very similar device to promising results. There’s some more details about the project, but it never left the proof of concept stage despite being awarded two best paper awards. We wonder why it hadn’t been made into a commercial product for 5 years, but we’re glad it’s finally here for us to tinker with it.

E-paper is notorious for having very low refresh rates when compared to more conventional screens, much more so when driven in this method, but there are ways to speed them up a bit. Nevertheless, even when used as designed, they’re perfectly suited for being used in clocks which are easy on the eyes without a glaring backlight.

[Thanks Steveww for the tip!]