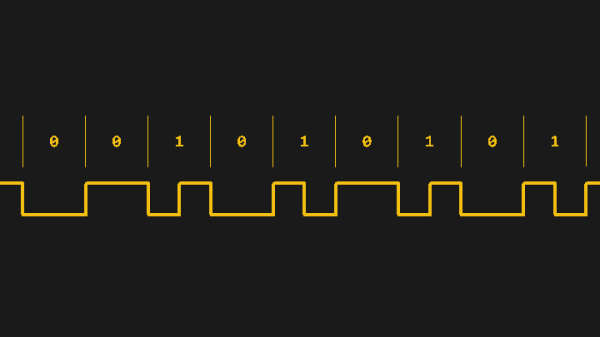

We often take our “SoftwareSerial” libraries for granted, and don’t investigate what goes on under the hood — until they fail us, at least. Would you like to learn how to harness the power of interrupt-driven bitbanging? [Jim Mack] teaches us how to make our protocol implementations fly using the LTC protocol as a springboard.

LTC (Linear/[Longitudinal] TimeCode) is a widely-used and beautifully-crafted protocol that tends to fly under our radar, and is one that hackers could learn plenty from. It’s used for synchronization of audio/video devices during media production and playback. LTC’s signal is almost digital but not quite: it doesn’t need a clock, and it has no polarity. Additionally, it mimics an audio signal really well, you can decode it at any playback speed, and many other benefits and quirks that [Jim] outlines. You do need to maintain the timings, though, and [Jim]’s article shows us how to keep them right while not inconveniencing your primary tasks.

Continue reading “Animate Arcane Protocols With Interrupt-Backed Bitbanging”