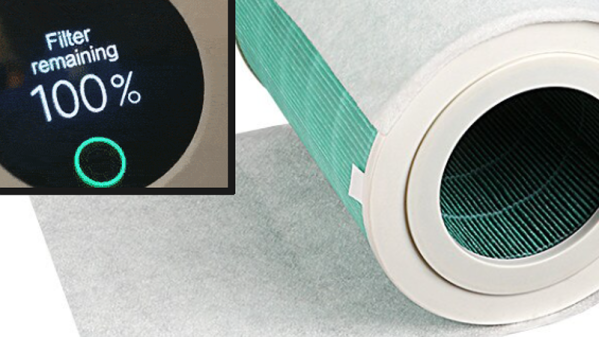

[Flamingo-tech]’s Xiaomi air purifier has a neat safety feature: it will refuse to run if a filter needs replacement. Of course, by “neat” we mean “annoying”. Especially when the purifier sure seems to judge a filter to be useless much earlier than it should. Is your environment relatively clean, and the filter still has legs? Are you using a secondary pre-filter to extend the actual filter’s life? Tough! Time’s up. Not only is this inefficient, but it’s wasteful.

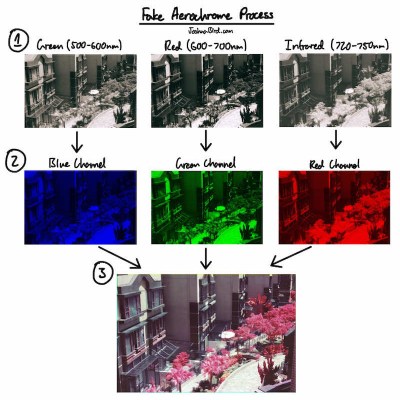

Every Xiaomi filter contains an NTAG213 NFC tag with a unique ID and uses a unique password for communications, but how this password was generated (and therefore how to generate new ones) was not known. This meant that compatible tags recognized by the purifier could not be created. Until now, that is. [Flamingo-tech] has shared the discovery of how Xiaomi generates the password for communication between filter and purifier.

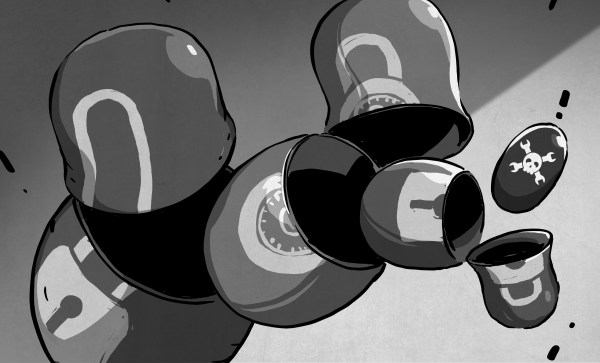

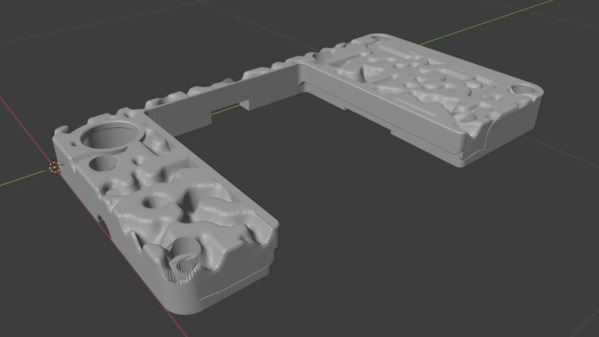

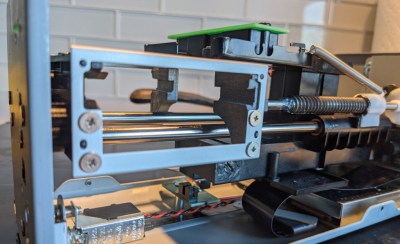

[Flamingo-tech] has long been a proponent of fooling Xiaomi purifiers into acting differently. In the past, this meant installing a modchip to hijack the DRM process. That’s a classic method of getting around nonsense DRM on things like label printers and dishwashers, but in this case, reverse-engineering efforts paid off.

It’s now possible to create simple NFC stickers that play by all the right rules. Is a filter’s time up according to the NFC sticker, but it’s clearly still good? Just peel that NFC sticker off and slap on a new one, and as far as the purifier is concerned, it’s a new filter!

If you’re interested in the reverse-engineering journey, there’s a GitHub repository with all the data. And for those interested in purchasing compatible NFC stickers, [Flamingo-tech] has some available for sale.