You could be forgiven for thinking that laser cutters and engravers are purely two dimensional affairs. After all, when compared to something like your average desktop 3D printer, most don’t have much in the way of a Z axis: the head moves around at a fixed height over the workpiece. It’s not as if they need a leadscrew to push the photons down to the surface.

But it’s actually a bit more complicated than that. As [Martin Raynsford] explains in a recent post on his blog, getting peak performance out of your laser cutter requires the same sort of careful adjustment of the Z axis that you’d expect with a 3D printer. Unfortunately, the development of automated methods for adjusting this critical variable on lasers hasn’t benefited from the same kind of attention that’s been given to the problem on their three dimensional counterparts.

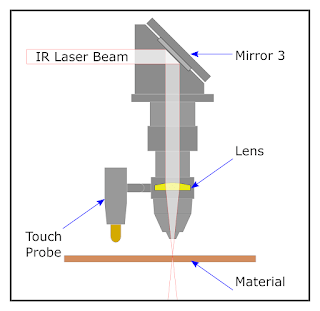

Ultimately, it’s a matter of focus. The laser is at its most powerful when its energy is concentrated into the smallest dot possible. That means there’s a “sweet spot” in front of the lens where cutting and engraving will be the most efficient; anything closer or farther away than that won’t be as effective. As an example, [Martin] says that distance is exactly 50.3 mm on his machine.

Ultimately, it’s a matter of focus. The laser is at its most powerful when its energy is concentrated into the smallest dot possible. That means there’s a “sweet spot” in front of the lens where cutting and engraving will be the most efficient; anything closer or farther away than that won’t be as effective. As an example, [Martin] says that distance is exactly 50.3 mm on his machine.

The problem comes when you start cutting materials of different thicknesses. Just a few extra millimeters between the laser and your target material can have a big difference on how well it cuts or engraves. So the trick is maintaining that perfect distance every time you fire up the laser. But how?

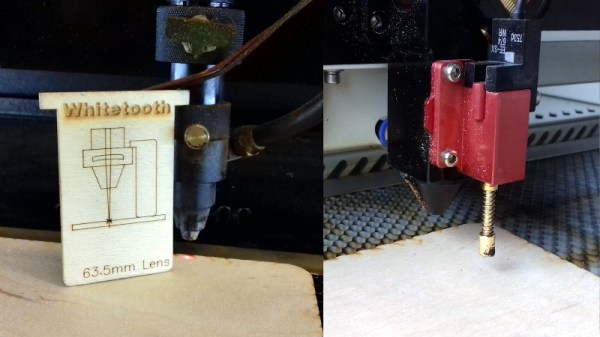

One way to automate this process is a touch probe, which works much the same as it does on a 3D printer. The probe is used to find where the top of the material is, and the ideal distance can be calculated from that point. But in his experience, [Martin] has found these systems leave something to be desired. Not only do they add unnecessary weight to the head of the laser, but the smoke residue that collects on the touch probe seems to invariably mar whatever surface you’re working on with its greasy taps.

In his experience, [Martin] says the best solution is actually the simplest. Just cut yourself a little height tool that’s precisely as long as your laser’s focal length. Before each job, stick the tool in between the laser head and the target to make sure you’re at the optimal height.

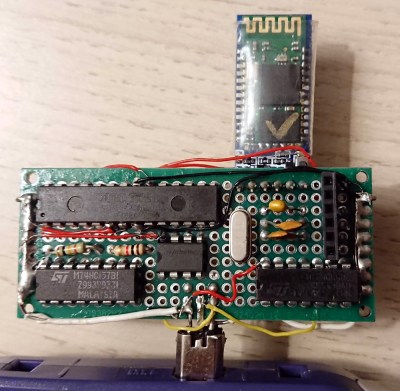

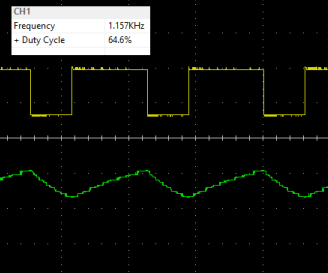

On entry level lasers, adjusting the Z height is likely to involve turning some screws by hand. But you can always add a motorized Z table to speed things up a bit. Of course, you’ll still need to make sure your X and Y alignment is correct. Luckily, [Martin] has some tips for that as well.