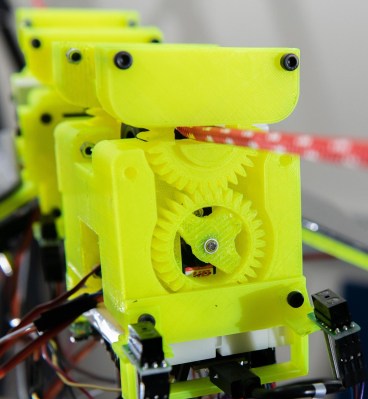

For moving about in the real world, robots can crawl along the ground or take to the sky. Both options have disadvantages, with obstacles being a problem on the ground and flying being very energy intensive. What we don’t often see are robots that move along aerial cables, which can offer the best of both worlds for certain use cases. Taking inspiration from a sloth’s slow and efficient movement through the trees, researchers from Georgia Tech created a robot to crawl slowly along a cable network and monitor the world around it, and of course named it Slothbot.

Slothbot trades speed for efficiency, letting it operate for very long periods on solar power alone. It does require the set up and maintenance of a cable network, but that brings the advantage of no obstacles, and the ability to stop and recharge. To us the most interesting feature is the cable switching mechanism, that allows it to navigate its way along a web of interconnected cables.

Ring gears with a section removed hold the upper part of the pulley mechanism, but can rotate it’s opening to the left or right to allow an interconnecting cable to pass through, The body is in two pieces, with an actuated hinge in the middle to allow it to turn onto a different cable section. Each section of the body also has a powered wheel which pushes up against the cable and moves the robot along slowly. Not surprisingly, researchers say that making the cable switching mechanism reliable is the biggest challenge. It does look like the current design would not work well with thicker cable joints. Watch the video after the break for a better look at the mechanism Continue reading “Slothbot Lives Up To Its Name”

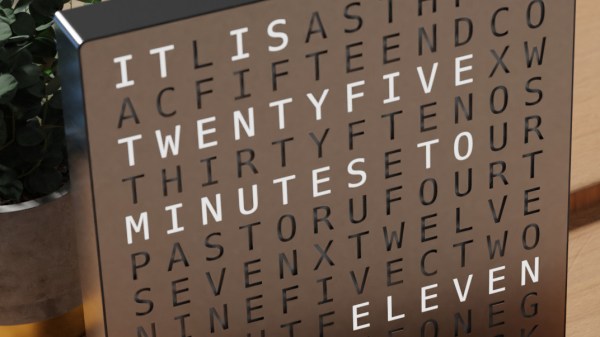

Inspired by the picture of a commercially available word clock, [Yasa] remembered the fun he had back in 2012 when he made

Inspired by the picture of a commercially available word clock, [Yasa] remembered the fun he had back in 2012 when he made