As an avid fan of the show Dr Who, [Adam Sifounakis] saw a model for a laser-cut TARDIS that piqued his curiosity that eventually grew into a multi-week project involving multiple setbacks, missteps, revamps and — finally — gratification. Behold, his sound activated TARDIS.

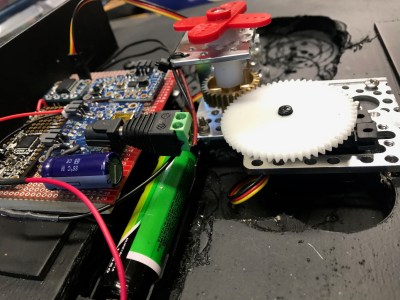

First and foremost, assembling and painting the model was a fun puzzle — despite a few trips to the store — with a little backtracking on the painting due to impatience. Next, the creation of a pulsing soft white LED circuit timed with an audio clip to really sell the image of a mini-TARDIS proved to be a tedious ordeal, paying off in the end with a satisfying glow through the vellum-diffused windows on the model.

How to trigger the lights? [Sifounakis] initially wanted a capacitive sensor to trigger the sound effects, but that way lay dragons — and madness — so he went with snap-activated effect to activate the TARDIS like the Doctor himself. After struggling with building his own microphone setup, he switched to an electret mic with adjustable gain which worked like a charm. Setting up this TARDIS’ Adafruit Pro Trinket brain involved a snag or two, and after that it was smooth sailing!

Until he hit another hitch with the power circuit too, that is. Luckily enough, adding a capacitor to give the circuit a bit more juice on boot solved the issue. All that was left to do was dismantle and rebuild his circuit after all this troubleshooting and substitutions, and — finally — install it in his model.

With much satisfaction and a final rework of the LED pulsing effect, it was done. Check it out!

Continue reading “Building This TARDIS Is Anything But A Snap”