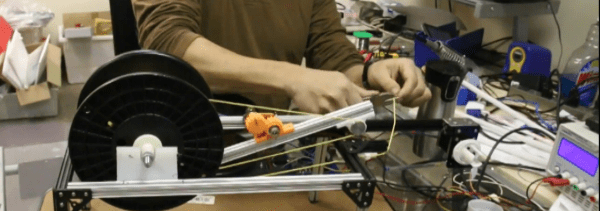

[Solarbotics] have shared a video of their DIY wire spooler that uses OpenBeam hardware plus some 3D printed parts to flawlessly spool wire regardless of spool size mismatches. Getting wire from one spool to another can be trickier than it sounds, especially when one spool is physically larger than the other. This is because consistently moving wire between different sizes of spools requires that they turn at different rates. On top of that, the ideal rate changes as one spool is emptying and the other gets larger. The wire must be kept taut when moving from one spool to the next; any slack is asking for winding problems. At the same time, the wire shouldn’t be so taut as to put unnecessary stress on it or the motor on the other end.

There aren’t any build details but the video embedded below gives a good overview and understanding of the whole system. In the center is a tension bar with pulleys on both ends though which the wire feeds. This bar pivots at the center and takes up slack while its position is encoded by turning a pot via a 3D printed gear. Both spools are motor driven and the speed of the source spool is controlled by the position of the tension bar. As a result, the bar automatically takes up any slack while dynamically slowing or speeding the feed rate to match whatever is needed.

Continue reading “DIY Wire Spooler With Clever Auto-Tensioning System”