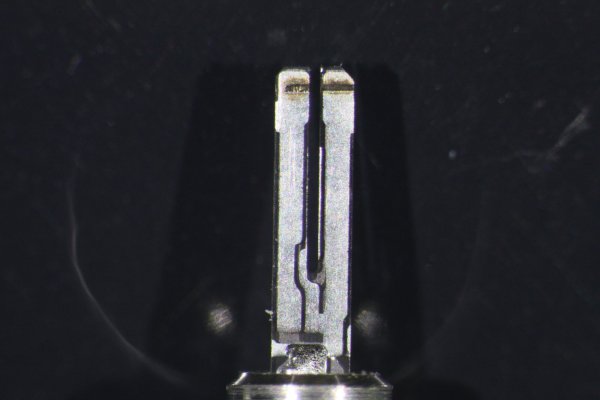

It’s hard to resist the temptation to tear apart a shiny new gadget, but fortunately, iFixIt often does it for us. This helps to keep our credit cards safe, and reveal the inner workings of new stuff. That is definitely the case with the Microsoft Surface Book teardown that they have just published. Apart from revealing that it is pretty much impossible to repair yourself, the teardown reveals the mechanism for the innovative hinge and lock mechanism. The lock that keeps the tablet part in place when in laptop mode is held in place by a spring, with the mechanism being unlocked by a piece of muscle wire.

We are no strangers to muscle wire (AKA Nitinol wire or Shape Metal Alloy, as it is sometimes called) here: we have posted on its use in making strange robots, robotic worms and walls that breathe. Whatever you call it, it is fun stuff. It is normally a flexible wire, but when you apply a voltage, it heats up and contracts, much like the muscles in your body. Remove the voltage, and the wire cools and reverts to its former shape. In the Microsoft Surface Book, a single loop of this wire is used to retract the lock mechanism, releasing the tablet part.

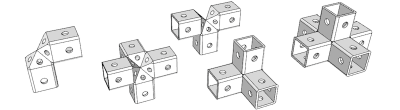

Unfortunately, the teardown doesn’t go into much detail on how the impressive hinge of the Surface Book works. We would like to see more detail on how Microsoft engineered this into the small space that it occupies. The Verge offered some details in a post at launch, but not much in the way of specifics beyond calling it an “articulated hinge”.

UPDATE: This post was edited to clarify the way that muscle wire works. 11/4/15.