3D printers are great for rapid prototyping, but they’re not usually what you’d call… portable. For [Malte Schrader], that simply wouldn’t do – thus, the X-printer was born!

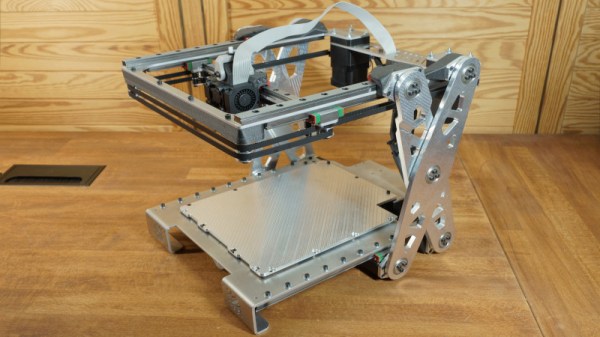

The X-printer is a fused-deposition printer built around a CoreXY design. Its party piece is its folding concertina-style Z-axis, which allows the printer to have a build volume of 160x220x150mm, while measuring just 300x330x105mm when folded. That’s small enough to fit in a backpack!

Getting the folding mechanism to work took some extra effort, with the non-linear Z-axis requiring special attention in the firmware. The printer runs Marlin 1, chosen for its faster compile time over Marlin 2. Other design choices are made with an eye to ruggedness. The aluminium frame isn’t as light as it could be, but adds much needed rigidity and strength. We’d love to see a custom case that you could slide the printer into so it would be protected while stowed.

It’s a build that shows there’s still plenty to be gained from homebrewing your own printer, even in the face of unprecedented options on the market today. We’ve seen other unique takes on the portable printer concept before, too. Video after the break.