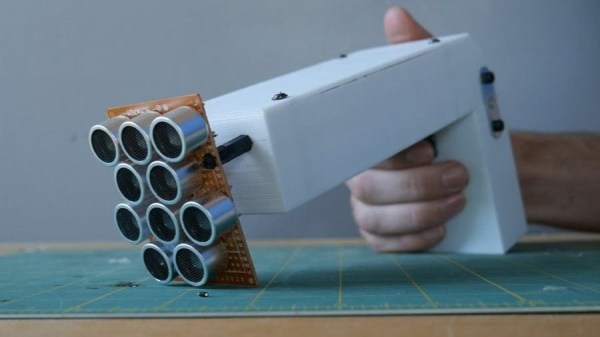

When we think of a speaker, we are likely to imagine a paper cone with a coil of wire somewhere at the bottom of it suspended in a magnetic field. It’s a hundred-plus-year-old technology that has been nearly perfected. The moving coil is not however the only means of turning an electrical current into a sound. A number of components will make a sound when exposed to audio, including to the surprise of [Eric], the humble incandescent light bulb. He discovered when making an addressable driver for them that he could hear the PWM frequency when they lit up, so he set about harnessing the effect for use as a speaker.

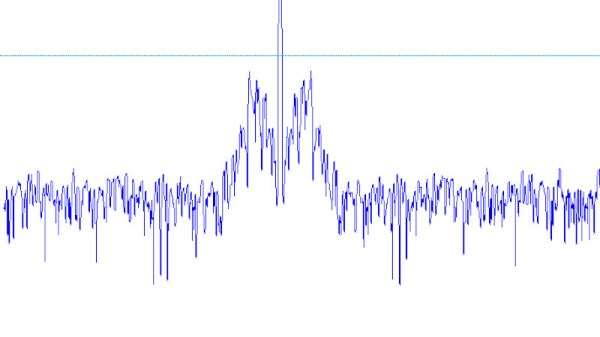

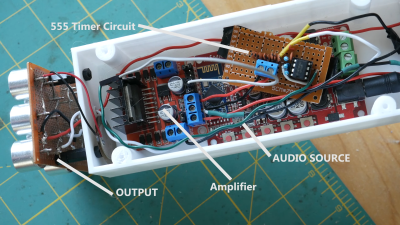

Using an ESP32 board and with a few false starts due to cheap components, he started with MIDI files and ended up with PWM frequencies. It’s an interesting journey into creating multiple PWM channels from an ESP32, and he details some of his problems along the way. The result is the set of singing light bulbs that can be seen in the video below the break, which he freely admits is probably the most awful 50 W speaker that he could have made. That however is not the point of such an experiment, and we applaud him for doing it.

For more MIDI-based tomfoolery, take a look at the PCB Tesla coil.