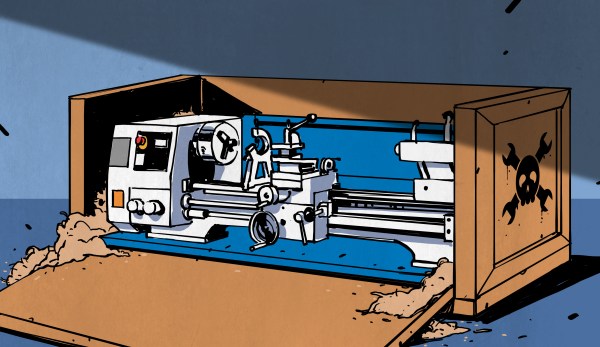

Let’s say you’ve recently bought a lathe and set it up in your shop. Maybe you’ve even gone and leveled it like a boss. You’re ready to make chips, right? Well, not so fast. As real machinists will tell you, you can use all the levels and lasers and whatever that you want, but the proof is in the cut. Precision leveling gets your machine in the ballpark (machinists have very small ballparks) but the final step to getting a machine to truly perform well is to cut a test bar. This is a surefire way to eliminate any last traces of twist in the bed.

There are two types of test bars. One is for checking headstock-to-ways alignment, which is what we’re doing here. There’s another type used for checking tailstock alignment, but that’s a subject for another day.

Continue reading “Lathe Headstock Alignment: Cutting A Test Bar”