We’ve noticed waving cats in restaurants and stores for years, but even the happy bobbing of their arm didn’t really catch our attention. Maybe [Josh] had seen a couple more than we have when it occurred to him to take one apart to see how they work. They are designed to run indoors from unreliable light sources and seem to bob along forever. How do the ubiquitous maneki-neko get endless mechanical motion from one tiny solar cell?

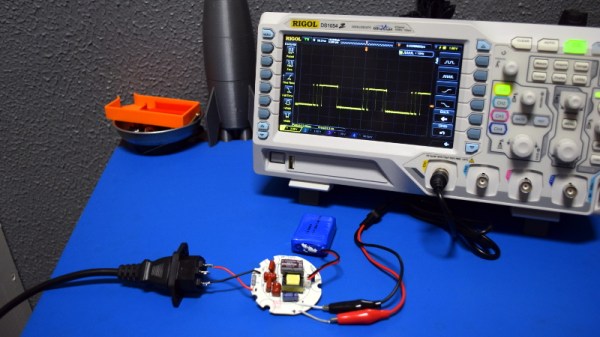

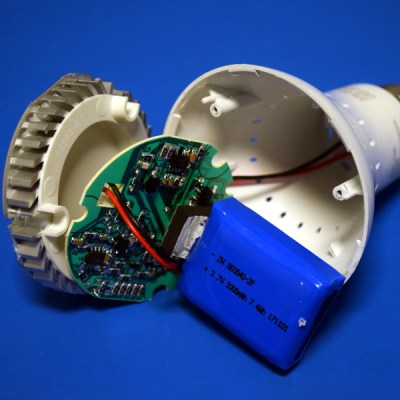

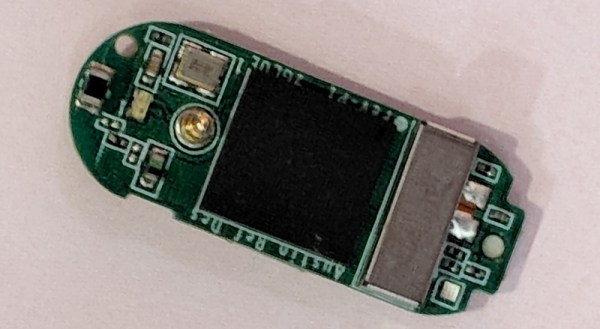

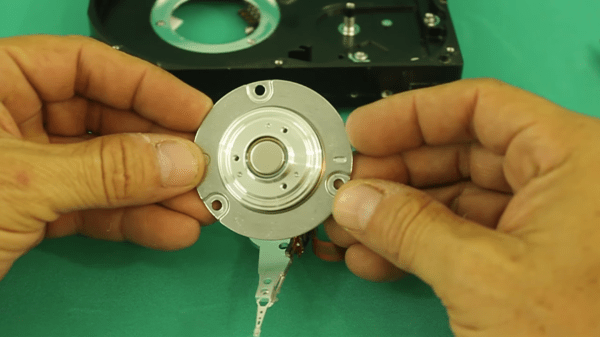

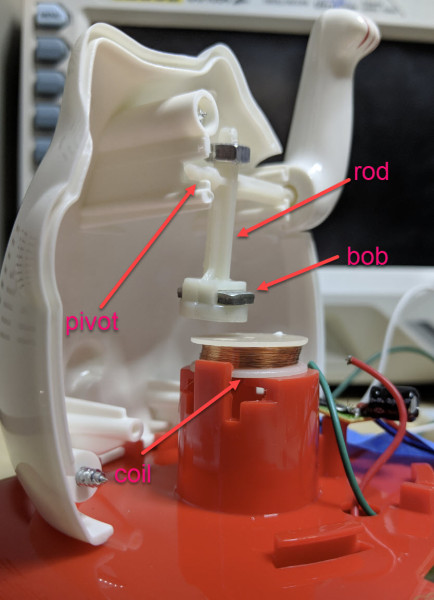

Perhaps unsurprisingly given the prevalence and cost of these devices, the answer is quite simple. The key interaction is between a permanent magnet mounted to the end of the waving arm/pendulum and a many-turn wire coil attached to the body. As the magnet swings over the coil, its movement induces a voltage. A small blob of analog circuitry reacts by running current through the coil. The end effect is that it “senses” the magnet passing by and gives it a little push to keep things moving. As long as there is light the circuit can keep pushing and the pendulum swings forever. If it happens to stop a jolt from the coil starts the pendulum swinging and the rest of the circuit takes over again. [Josh] points to a similar circuit with a very nice write up in an issue of Nuts and Volts for more detail.

Perhaps unsurprisingly given the prevalence and cost of these devices, the answer is quite simple. The key interaction is between a permanent magnet mounted to the end of the waving arm/pendulum and a many-turn wire coil attached to the body. As the magnet swings over the coil, its movement induces a voltage. A small blob of analog circuitry reacts by running current through the coil. The end effect is that it “senses” the magnet passing by and gives it a little push to keep things moving. As long as there is light the circuit can keep pushing and the pendulum swings forever. If it happens to stop a jolt from the coil starts the pendulum swinging and the rest of the circuit takes over again. [Josh] points to a similar circuit with a very nice write up in an issue of Nuts and Volts for more detail.

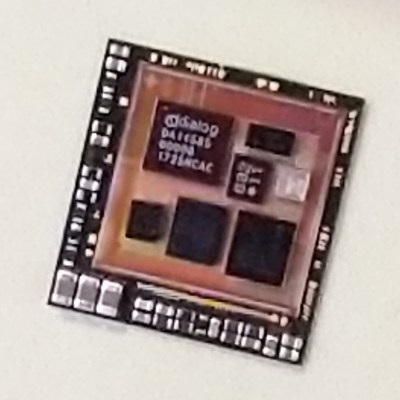

We’ve covered [Josh]’s toy teardowns before and always find this category of device particularly interesting. Toys and gadgets like the maneki-neko are often governed by razor-thin profit margins and as such must satisfy an extremely challenging intersection of product constraints, combining simple design and fabrication with just enough reliability to not be a complete disappointment.

For more, watch [Josh] describe his method in person after the break, or try flashing his code to an Arduino and make a waving cat of your own.

Continue reading “An Electromagnet Brings Harmony To This Waving Cat”