When it has become so common for movies and television to hyper-sensationalize engineering, and to just plain get things wrong, here’s a breath of fresh air. There’s a Sci-Fi show out right now that wove 3D printing into the story line in a way that is correct, unforced, and a fitting complement to that fictional world.

With the amount of original content Netflix is pumping out anymore, you may have missed the fact that they’ve recently released a reboot of the classic Lost in Space series from the 1960’s. Sorry LeBlanc fans, this new take on the space traveling Robinson family pretends the 1998 movie never happened, as have most people. It follows the family from their days on Earth until they get properly lost in space as the title would indicate, and is probably most notable for the exceptional art direction and special effects work that’s closer to Interstellar than the campy effects of yesteryear.

With the amount of original content Netflix is pumping out anymore, you may have missed the fact that they’ve recently released a reboot of the classic Lost in Space series from the 1960’s. Sorry LeBlanc fans, this new take on the space traveling Robinson family pretends the 1998 movie never happened, as have most people. It follows the family from their days on Earth until they get properly lost in space as the title would indicate, and is probably most notable for the exceptional art direction and special effects work that’s closer to Interstellar than the campy effects of yesteryear.

But fear not, Dear Reader. This is not a review of the show. To that end, I’ll come right out and say that Lost in Space is overall a rather mediocre show. It’s certainly gorgeous, but the story lines and dialog are like something out of a fan film. It’s overly drawn out, and in the end doesn’t progress the overarching story nearly as much as you’d expect. The robot is pretty sick, though.

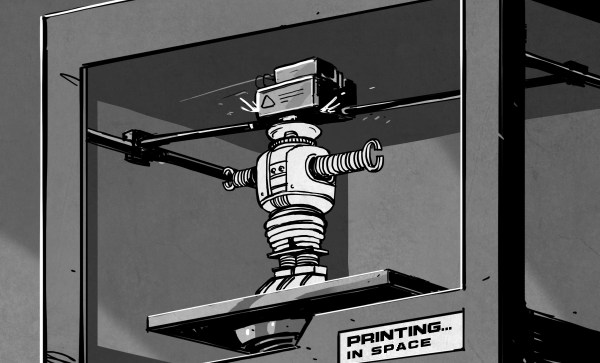

No, this article is not about the show as a whole. It’s about one very specific element of the show that was so well done I’m still thinking about it a month later: its use of 3D printing. In Lost in Space, the 3D printer aboard the Jupiter 2 is almost a character itself. Nearly every member of the main cast has some kind of interaction with it, and it’s directly involved in several major plot developments during the season’s rather brisk ten episode run.

I’ve never seen a show or movie that not only featured 3D printing as such a major theme, but that also did it so well. It’s perhaps the most realistic portrayal of 3D printing to date, but it’s also a plausible depiction of what 3D printing could look like in the relatively near future. It’s not perfect by any means, but I’d be exceptionally interested to hear if anyone can point out anything better.

Continue reading “Lost In Space Gets 3D Printing Right” →