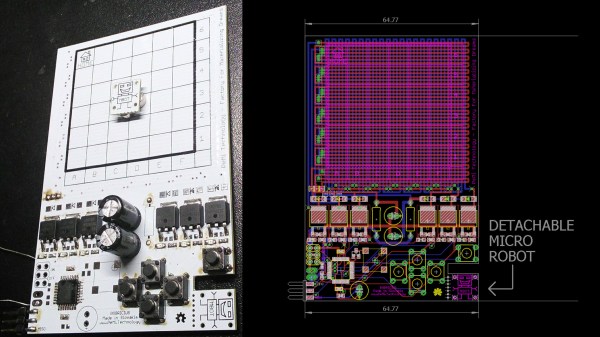

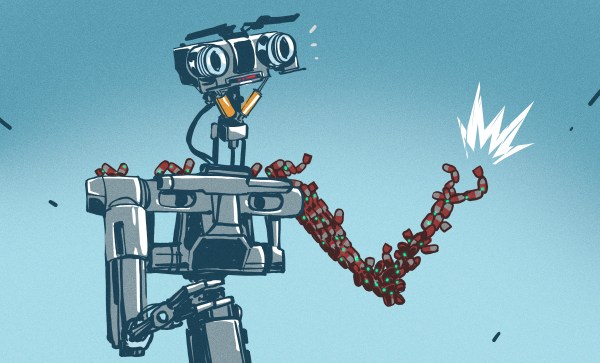

Whether with projects featured here or out in the real world, we have a tendency to focus most upon the end product. The car, solar panel, or even robot. But there’s a lot more going on behind the scenes that needs to be taken care of as well, whether it’s fuel infrastructure to keep the car running, a semiconductor manufacturer to create silicon wafers, or a control system for the robot. This project is one of the latter: a human interface device for a robot arm that is completely DIY.

While robots are often automated, some still need human input. The human input can be required all the time, or can be used to teach the robot initially how to perform a task which will then be automated. This “keyboard” of sorts built by [Ahmed] comes with a joystick, potentiometer, and four switch inputs that are all fully programmable via an Arduino Due. With that, you can perform virtually any action with whatever type of robot you need, and since it’s based on an Arduino it would also be easy to expand.

The video below and project page have all the instructions and bill of materials if you want to roll out your own. It’s a pretty straightforward project but one that might be worth checking out since we don’t often feature controllers for other things, although we do see them sometimes for controlling telescopes rather than robots.