If you are a college student and you get too many parking fines, you are going to get in trouble. But one school didn’t count on students hacking their high tech parking violation deterrent. Some even got free internet from the devices.

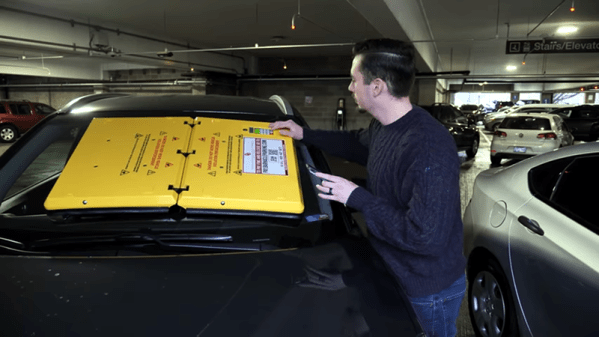

You pay your taxes or — in the case of students — your tuition. But still, the city or university wants you to pay to park your car. In the old days, you’d get your car towed. But the people running the parking lot don’t really like having to share the fees they charge you with a tow truck driver. Many places clamp a device to your tire that makes it impossible to drive. Oklahoma University decided that was too much trouble, also, so they turned to Barnacle. Barnacle is a cheaper alternative to the old parking clamp. In sticks to your windshield so you can’t see to drive. The suction cups have an air pump to keep them secure and a GPS squeals if you move the car with it on there anyway.

Continue reading “Students Use Low Tech Hacks On High Tech Parking Enforcer”