A weather station can be anything from a fun home science exercise, all the way up to a useful tool for planning and weather prediction. [Rob Ward] is one such person who has developed their own weather station, and it recently got a wireless upgrade.

We first featured [Rob]’s work back in 2018, noting that a largely 3D-printed weather station was a particularly useful tool for the home experimenter. The utility of this is now improved, with the addition of a 433 MHz wireless link from the weather sensors back to the base station. Over on Github, [Rob] does a great job of explaining the basics of the Manchester encoding scheme used, and has developed a system that can decode signals from Oregon Scientific weather stations, too.

[Rob] uses the weather station to report weather conditions at Lake Tyers Beach, providing useful information for anyone in the area who might be considering a visit to the coast. It’s not quite as fun as asking whoever’s around on the CB road channel, but it’s a darn sight more accurate for your trouble. Video after the break.

Continue reading “3D Printed Weather Station Gets A Wireless Upgrade”

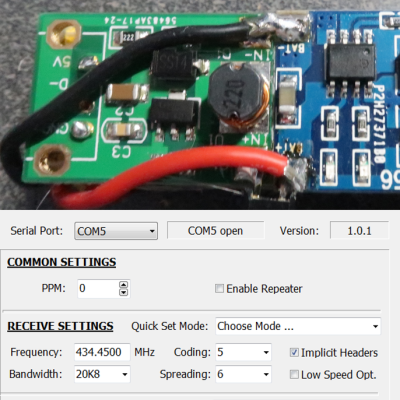

[Dave Akerman]’s interest in high-altitude projects means he is no stranger to long-range wireless communications, for which LoRa is amazingly useful. LoRa is a method of transmitting at relatively low data rates with low power over long distances.

[Dave Akerman]’s interest in high-altitude projects means he is no stranger to long-range wireless communications, for which LoRa is amazingly useful. LoRa is a method of transmitting at relatively low data rates with low power over long distances.