It’s the eternal question hackers face: do you built it, or do you buy it? The low cost and high availability of electronic gadgets means we increasingly take the latter option. Especially since it often ends up that building your own version will cost more than just buying a commercial product; and that’s before you factor in the time you’ll spend working on it.

But such concerns clearly don’t phase [Andrea Cavalli]. Sure he could just buy a scientific calculator, but it wouldn’t really be his scientific calculator. Instead, he’s taking the scenic route and building his own scientific calculator from scratch. The case is 3D printed, the PCB is custom, and even the software is his own creation.

But such concerns clearly don’t phase [Andrea Cavalli]. Sure he could just buy a scientific calculator, but it wouldn’t really be his scientific calculator. Instead, he’s taking the scenic route and building his own scientific calculator from scratch. The case is 3D printed, the PCB is custom, and even the software is his own creation.

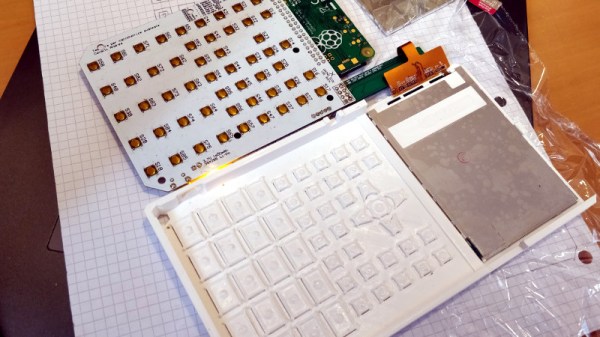

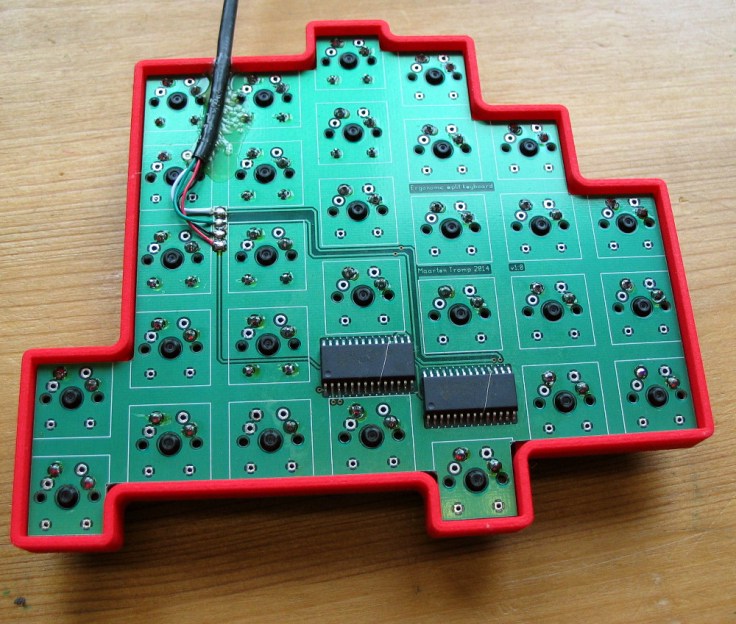

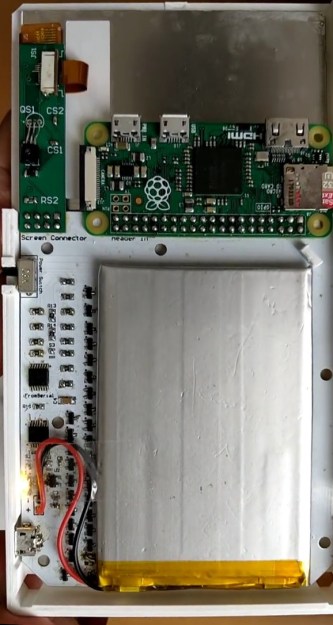

His PCB hooks right up to the GPIO pins of the internal Raspberry Pi Zero, making interfacing with the dome switch keyboard very easy. The board also holds the power management hardware for the device, including the physical power switch, USB connection for charging, and TPS79942DDCR linear regulator.

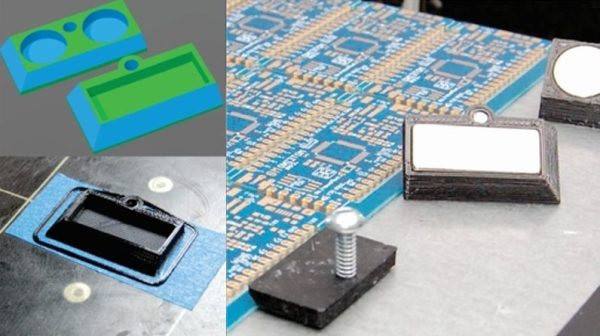

The case, including the buttons, is entirely 3D printed. At this point the buttons don’t actually have any labels on them, which presumably makes the calculator more than a little challenging to use, but no doubt [Andrea] is working on that for a later revision of the hardware. A particularly nice detail is the hatch to access the Pi’s micro SD card, making it easy to update the software or completely switch operating systems without having to take the calculator apart.

After the kernel messages scroll by, the Pi boots right into the Java calculator environment. This gives the user a fairly standard scientific calculator experience, complete with nice touches like variable highlighting. The Mario mini-game probably isn’t strictly required, but if you’re writing the code for your own calculator you can do whatever you want.

Here at Hackaday we’ve seen a calculator that got a Raspberry Pi upgrade, a classic scientific calculator emulated with an Arduino, and of course we’ve raved about the NumWorks open source graphing calculator. Even with such stiff competition, we think this project is well on its way to being one of the most impressive calculators we’ve ever come across.

Continue reading “DIY Scientific Calculator Powered By Pi Zero”