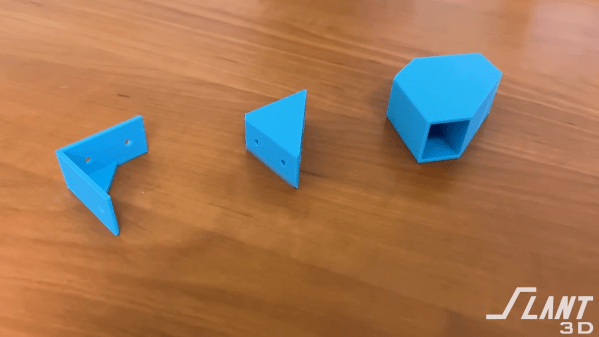

On the “hack/not-a-hack” scale, a 3D printed bracket for aluminum extrusions is — well, a little boring. Such connectors are nothing you couldn’t buy, and even if you insisted on printing them instead, Printables and Thingiverse are full of ready-to-use designs. So why would you waste your precious time and effort rolling your own?

According to production 3D printing company [Slant 3D], a lot of times, we forget to take advantage of the special capabilities of 3D printing. The design progression of the L-bracket shown is a perfect example; it starts as a simple L, moves on to a more elaborate gusseted design, and eventually into a sturdy sold block design that would be difficult to make with injection molding thanks to shrinkage but is no problem for a 3D printer. Taking that a step further, the bracket morphs into a socketed design, taking advantage of what 3D printers can do by coming up with a part that reduces assembly time and fastener count while making a more finished, professional look.

Again, this isn’t really about the bracket. Rather, it’s about a different way of thinking about your designs and leveraging the unique capabilities of 3D printers relative to other mass-production methods, like injection molding. We’ve covered some of [Slant 3D]’s high-volume design insights before, such as including living hinges and alternatives of pins and holes for assembling printed parts. Continue reading “Better 3D Prints, Courtesy Of A Simple Mass-Produced Bracket”

The printer is a gargantuan thing, using an aluminium frame and a familiar Cartesian layout. It boasts a build volume of 1110 mm x 1110 mm x 2005 mm, making it more than big enough to print human-sized statues. Dogs, cats, and some great apes may be possible, too.

The printer is a gargantuan thing, using an aluminium frame and a familiar Cartesian layout. It boasts a build volume of 1110 mm x 1110 mm x 2005 mm, making it more than big enough to print human-sized statues. Dogs, cats, and some great apes may be possible, too.