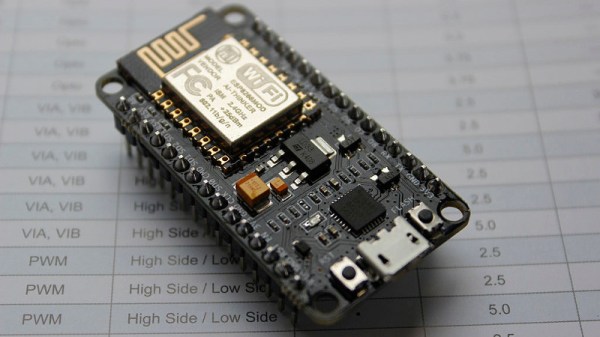

The ESP8266 has become incredibly popular in a relatively short time, and it’s no wonder. Cheap as dirt, impressively powerful, Arduino-compatible, and best of all, includes Wi-Fi right out of the box. But for all its capability and popularity, it’s still lagging behind the Arduino in at least one respect. Namely, the vast collection of add-on “Shields” which plug into the Arduino to add everything from breadboards to GPS receivers.

Until such time as the free market decides to pick up the pace and start making standardized shields for the various ESP8266 development boards, it looks as if hackers are going to have to pick up the slack. [Rui Santos] has put together a very detailed step-by-step guide on the creation of a simple shield for the popular Wemos D1 Mini board, which should give you plenty of inspiration for spinning up your own custom add-on modules.

Until such time as the free market decides to pick up the pace and start making standardized shields for the various ESP8266 development boards, it looks as if hackers are going to have to pick up the slack. [Rui Santos] has put together a very detailed step-by-step guide on the creation of a simple shield for the popular Wemos D1 Mini board, which should give you plenty of inspiration for spinning up your own custom add-on modules.

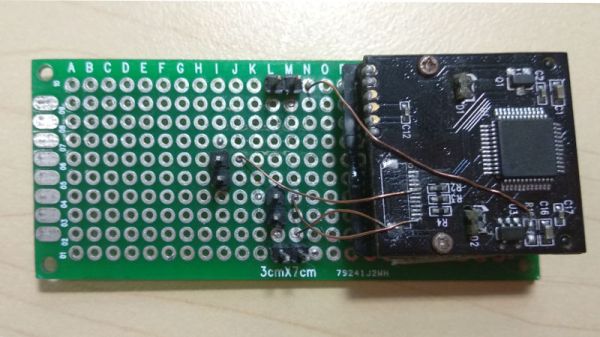

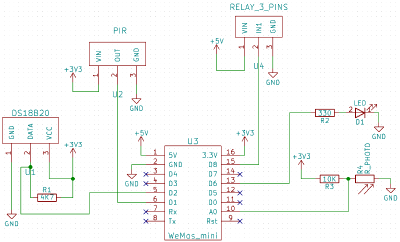

Presented as a written tutorial as well as a two part video, this guide covers everything from developing and testing your circuit on a breadboard to designing your PCB in KiCad and sending it off for fabrication. The end result is a professional looking PCB that matches the footprint of the stock D1 Mini and adds a DS18B20 temperature sensor, PIR motion detector, photoresistor, and some screw down terminals.

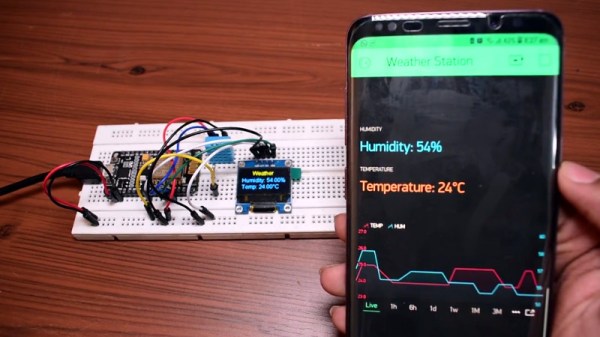

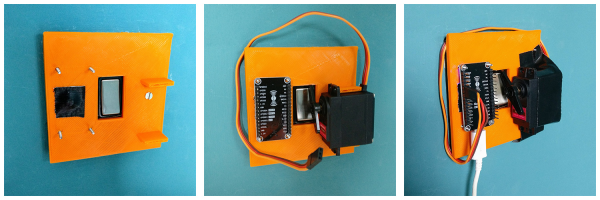

[Rui] goes on to show how you can utilize the new sensors shield via a web interface hosted on the ESP8266, and even wraps the whole thing up in a 3D printed enclosure. All worthwhile skills to check out if you’re looking to produce more cohesive finished products.

If you’re looking for a similar project for the ESP32, [Rui] has you covered there as well. You may also be interested in the series of ESP8266 tutorials we recently highlighted.