It’s with sadness that we note the passing at the age of 94 of the long-time Phillips engineer Lou Ottens, who is best known as the originator of the Compact Cassette audio tape format that was so ubiquitous through the later decades of the 20th century. Whether you remember cassettes as the format for 8-bit software, for teenage mixtapes on a Walkman, they began life at his hands in the early 1960s at the Phillips factory in Hasselt, Belgium.

Through a long career with the Dutch electronics company, he was responsible either directly or in part for a string of consumer electronic devices that we would see as ubiquitous over the latter half of the century. Before the cassette he had developed the company’s first portable reel-to-reel tape recorder, and in the 1970s while technical director of their audio division he led the team that would develop the CD. He was reported as saying that his great regret was not beating Sony to the development of the miniature cassette player that would be sold as the Walkman, but we’d suggest that the Walkman would not have been possible without the cassette in the first place.

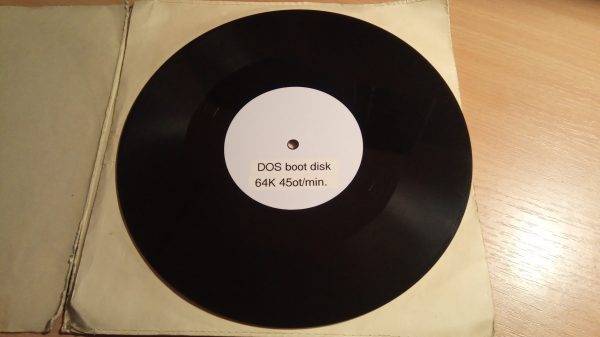

So next time you handle a cassette tape, spare a thought for Lou, an audio engineer whose work permeated so much of the last half-century.

Thanks [Carl] for the tip.

Images: Lou Ottens by Jordi Huisman CC BY-SA 4.0 and “An early Phillips cassette recorder” by mib18 CC BY-SA 3.0