Once upon a time, bailing out of a plane involved popping open the roof or door, and hopping out with your parachute, hoping that you’d maintained enough altitude to slow down before you hit the ground. As flying speeds increased and aircraft designs changed, such escape became largely impossible.

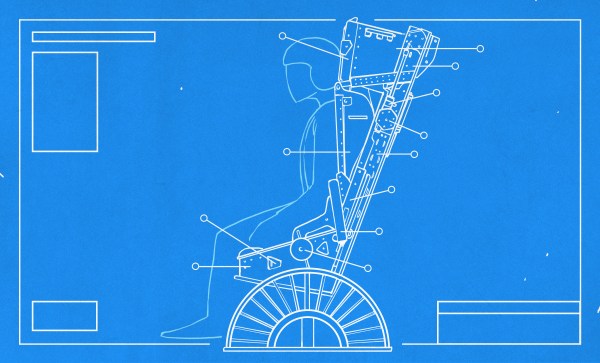

Ejector seats were the solution to this problem, with the first models entering service in the late 1940s. Around this time, the United Kingdom began development of a new fleet of bombers, intended to deliver its nuclear deterrent threat over the coming decades. The Vickers Valiant, the Handley Page Victor, and the Avro Vulcan were all selected to make up the force, entering service in 1955 through 1957 respectively. Each bomber featured ejector seats for the pilot and co-pilot, who sat at the front of the aircraft. The remaining three crew members who sat further back in the fuselage were provided with an escape hatch in the rear section of the aircraft with which to bail out in the event of an emergency.