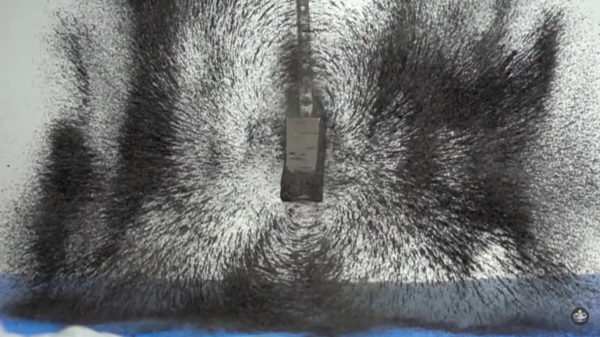

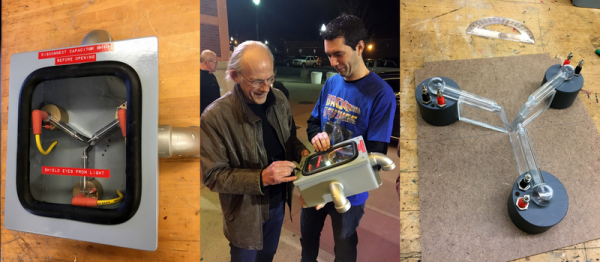

Often it feels as if soldering is deemed to be more of an art form than something that’s underpinned by the cold, hard reality of physics and chemistry. From organic chemistry with rosin, to the material properties of fragile gold bond wires and silicon dies inside IC packages and the effects of thermal stress on the different parts of an IC package, it’s a complicated topic that deserves a lot more attention than it usually gets.

A casual inquiry around one’s friends, acquaintances, colleagues and perfect strangers on the internet usually reveals the same pattern: people have picked up a soldering iron at some point, and either figured out what seemed to work through trial and error, or learned from someone else who has learned what seemed to work through trial and error. Can we say something scientific about soldering?

Continue reading “Get To Know The Physics Behind Soldering And The Packaging Of ICs”