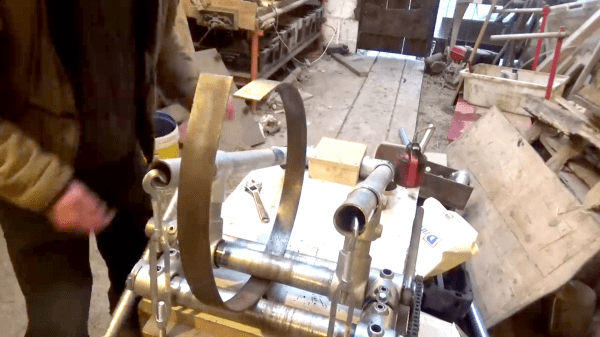

When you need to roll sheet or thin flat bar stock into an arc, you need a rolling machine, also known as a slip roll. If you’ve priced these lately, you’ll know that they can be rather expensive, especially if you are only going to use them for one or two projects. While building a fenced enclosure for his dog, [Tim] realized he could use steel fence posts and connectors to build his own slip roll for much less, and posted a video about it on his YouTube channel.

The key realization was that not only are the galvanized posts cheap and strong, but the galvanized coating would act as a lubricant to reduce wear, especially when augmented with a bit of grease. The build looks pretty straightforward, and a dedicated viewer could probably re-create a similar version with little difficulty. The stock fence connectors serve double-duty as both fasteners and bushings for the rollers, and a pair of turnbuckles supplies tension to the assembly.

The one tricky part is the chain-and-sprocket linkage which keeps the two bottom rollers moving in tandem. [Tim] cut sprockets from some plate steel with his plasma cutter, but mentions that similar sprockets can be found cheaply online and only need to be modified with a larger hole. Although most of the build is held together with set screws in the fence post fittings, the sprockets appear to be welded to the galvanized pipe. We’re sure [Tim] knows that welding galvanized steel can lead to metal fume fever, so we were hoping the video would caution viewers to remove the zinc coating on those parts before welding.

[Tim] demonstrates forming some 4 mm flat steel into circles, and the operation seems easy enough, especially given the inexpensive nature of this build. Overall, this seems like the sort of thing we could see ourselves trying on a lazy Saturday afternoon – it certainly seems like more fun than building a fence with the parts, so be sure to check out the video, after the break.