I loved my science courses when I was in Junior High School; we leaned to make batteries, how molecules combine to form the world we see around us, and basically I got a picture of where we stood in the scheme of things, though Quarks had yet to be discovered at the time.

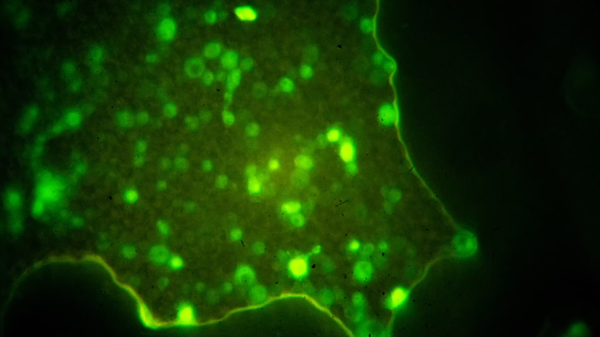

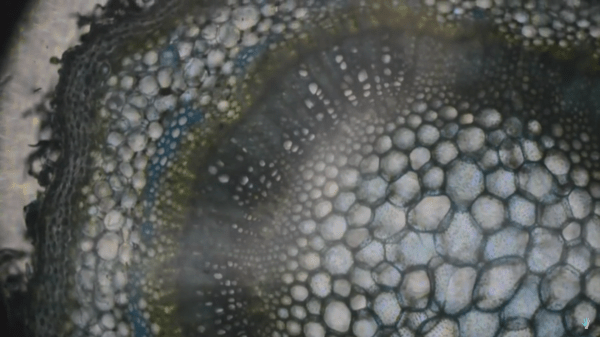

In talking with my son I found out that there wasn’t much budget for Science learning materials in his school system like we had back in my day, he had done very little practical hands-on experiments that I remember so fondly. One of those experiments was to look and draw the stages of mitosis as seen under a Microscope. This was amazing to me back in the day, and cemented the wonder of seeing cell division into my memory to this day, much like when I saw the shadow of one of Jupiter’s moons with my own eyes!

Now I have to stop and tell you that I am not normal, or at least was not considered to be a typical young’un growing up near a river in rural Indiana in the 60’s. I had my own microscope; it quite simply was my pride and joy. I had gotten it while I was in the first or second grade as a present and I loved the thing. It was just horrible to use in its later years as lens displaced, the focus rack became looser if that was possible, and dirt accumulated on the internal lens; and yet I loved it and still have it to this day! As I write this, I realize that it’s the oldest thing that I own. (that and the book that came with it).

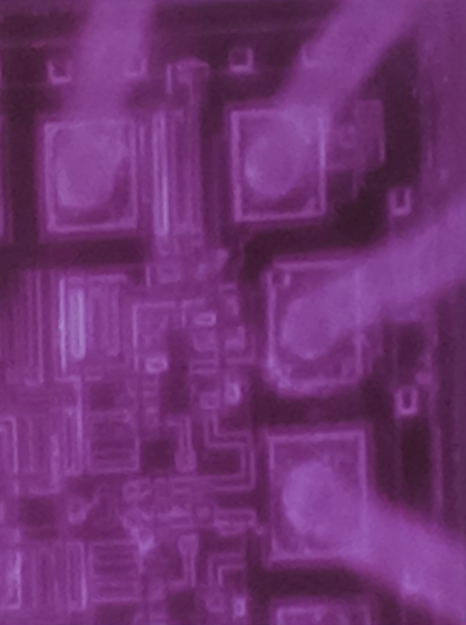

Today we have better tools and they’re pretty easy to come by. I want to encourage you to do some science with them. (Don’t just look at your solder joints!) Check out the video about seeing mitosis of onion cells through the microscope, then join me below for more on the topic!