Thermoforming — which includes vacuum-forming — has its place in a well-rounded workshop, and Mayku (makers of desktop thermoforming machines) have a short list of tips for getting the best results when 3D printing molds on filament-based printers.

A mold is put into direct, prolonged contact with a hot sheet of semi-molten plastic. If one needs a mold to work more than once, there are a few considerations to take into account. The good news is that a few simple guidelines will help get excellent results. Here are the biggest ones:

A mold is put into direct, prolonged contact with a hot sheet of semi-molten plastic. If one needs a mold to work more than once, there are a few considerations to take into account. The good news is that a few simple guidelines will help get excellent results. Here are the biggest ones:

- The smoother the vertical surfaces, the better. Since thermoforming sucks (or pushes) plastic onto and into a mold like a second skin, keeping layer heights between 0.1 mm and 0.2 mm will make de-molding considerably easier.

- Generous draft angles. Aim for a 5 degree draft angle. Draft angles of 1-2 degrees are common in injection molding, but a more aggressive one is appropriate due to layer lines giving FDM prints an inherently non-smooth surface.

- Thick perimeters and top layers for added strength. The outside of a mold is in contact with the most heat for the longest time. Mayku suggests walls and top layer between 3 mm to 5 mm thick. Don’t forget vent holes!

- Use a high infill to better resist stress. Molds need to stand up to mechanical stress as well as heat. Aim for a 50% or higher infill to make a robust part that helps resist deformation.

- Ensure your printer can do the job. 3D printing big pieces with high infill can sometimes lift or warp during printing. Use enclosures or draft shields as needed, depending on your printer and material.

- Make the mold out of the right material. Mayku recommends that production molds be printed in nylon, which stands up best to the heat and stress a thermoforming mold will be put under. That being said, other materials will work for prototyping. In my experience, even a PLA mold (which deforms readily under thermoforming heat) is good for at least one molding.

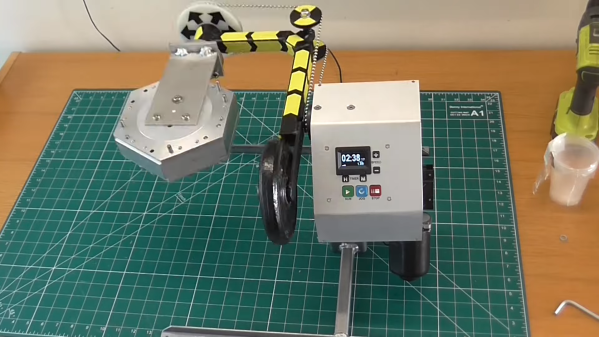

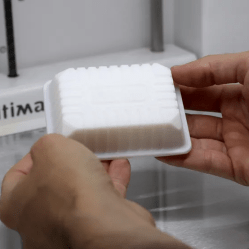

Thermoforming open doors for an enterprising hacker, and 3D printing molds is a great complement. If you’re happy being limited to small parts, small “dental” formers like the one pictured here are available from every discount overseas retailer. And of course, thermoforming is great for costumes and props. If you want to get more unusual with your application, how about forming your very own custom-shaped mirrors by thermoforming laminated polystyrene?