Creality, makers of the Ender series of 3D printers, have released a product called Wi-Fi Box meant to cheaply add network control to your printer. Naturally I had to order one so we could take a peek, but this is certainly not a product review. If you’re looking to control your 3D printer over the network, get yourself a Raspberry Pi and install Gina Häußge’s phenomenal OctoPrint on it. Despite what Creality might want you to believe, their product is little more than a poor imitation of this incredible open source project.

Even if you manage to get it working with your printer, which judging by early indications is a pretty big if, it won’t give you anywhere near the same experience. At best it’ll save you a few dollars compared to going the DIY route, but at the cost of missing out on the vibrant community of plugin developers that have helped establish OctoPrint as the defacto remote 3D printing solution.

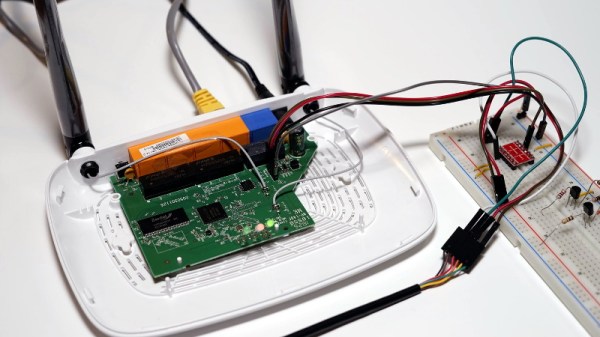

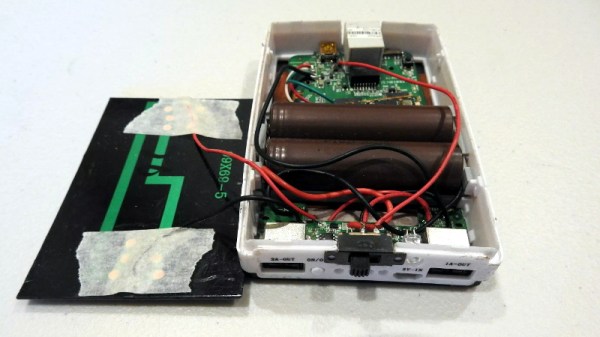

That being said, the hardware itself seems pretty interesting. For just $20 USD you get a palm-sized Linux computer with WiFi, Ethernet, a micro SD slot, and a pair of USB ports; all wrapped up in a fairly rugged enclosure. There’s no video output, but that will hardly scare off the veteran penguin wrangler. Tucked in a corner and sipping down only a few watts, one can imagine plenty of tasks this little gadget would be well suited to. Perhaps it could act as a small MQTT broker for all your smart home devices, or a low-power remote weather station. The possibilities are nearly limitless, assuming we can get into the thing anyway.

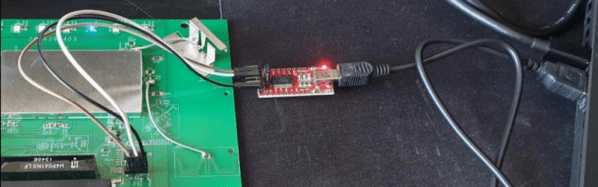

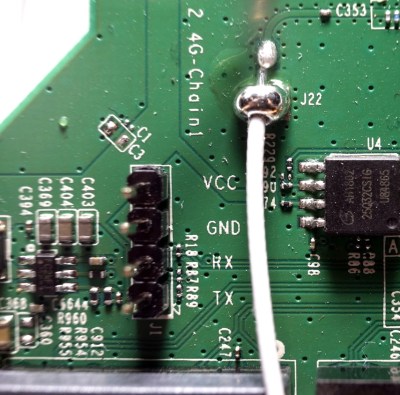

So what’s inside the Creality Wi-Fi Box, and how hard will it be to bend it to our will? Let’s take one apart and find out.