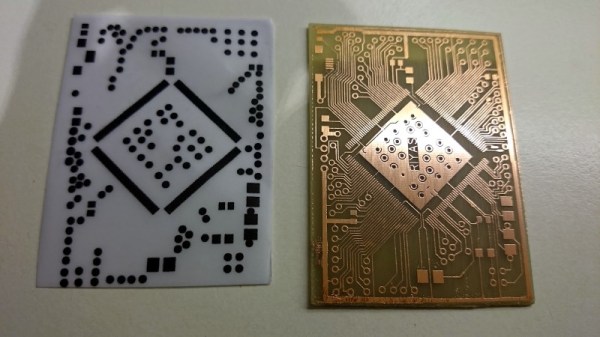

This project would fit in perfectly with #BadgeLife if someone could figure out a way to hang it from their neck. Inspired by Star Trek’s Starship Enterprise, [bobricius] decided to design and assemble a miniature space ship PCB model, complete with 40 blinking LEDs controlled by an ATtiny85.

While the design uses 0603, 0802, 3014, 4014, and 0805 LEDs, some substitutions can be made since the smallest LEDs can be difficult to solder. The light effects include a green laser, plasma coils, a deflector with scrolling blue LEDs, and the main plate and bridge for the space ship.

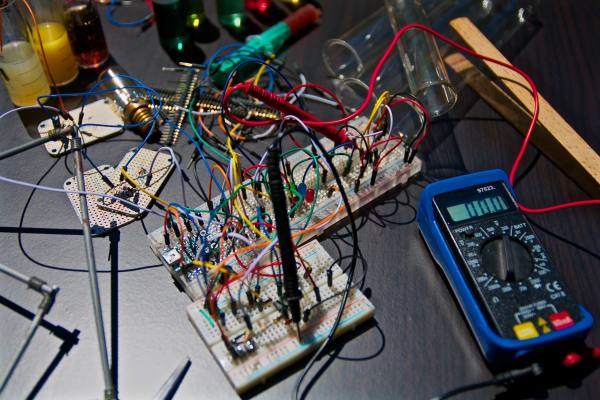

The LEDs are controlled by charlieplexing, a technique for driving LED arrays with relatively few I/O pins, different from traditional multiplexing. Charlieplexing allows n pins to drive n2−n LEDs, while traditional multiplexing allows n pins to drive (n/2)2 LEDs. (Here is the best explanation of Charlieplexing we’ve ever seen.)

Especially with the compiled firmware running on the MCU, the PCB model makes for an impressive display.

The only catch? Your Starship Enterprise can’t actually fly.