It’s time once again for another installment in “Milspec Teardown”, where we get to see what Uncle Sam spends all those defense dollars on. Battle hardened pieces of kit are always a fascinating look at what can be accomplished if money is truly no object. When engineers are given a list of requirements and effectively a blank check, you know the results are going to be worth taking a closer look.

Today, we have quite a treat indeed. Not only is this ID-2124 Howitzer Deflection-Elevation Data Display unit relatively modern (this particular specimen appears to have been pulled from service in June of 1989), but unlike other military devices we’ve looked at in the past, there’s actually a fair bit of information about it available to us lowly civilians. In a first for this ongoing series of themed teardowns, we’ll be able to compare the genuine article with the extensive documentation afforded by the ever fastidious United States Armed Forces.

Today, we have quite a treat indeed. Not only is this ID-2124 Howitzer Deflection-Elevation Data Display unit relatively modern (this particular specimen appears to have been pulled from service in June of 1989), but unlike other military devices we’ve looked at in the past, there’s actually a fair bit of information about it available to us lowly civilians. In a first for this ongoing series of themed teardowns, we’ll be able to compare the genuine article with the extensive documentation afforded by the ever fastidious United States Armed Forces.

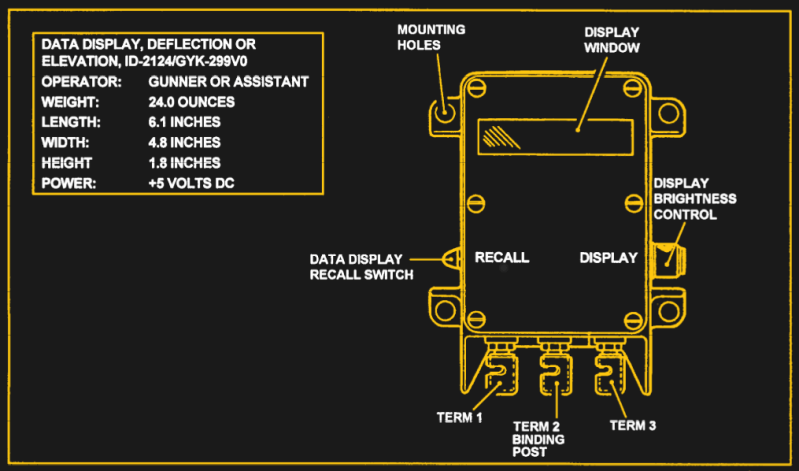

For example, rather than speculate wildly as to the purpose of said device, we can read the description directly from Field Manual 6-50 “TACTICS, TECHNIQUES, AND PROCEDURES FOR THE FIELD ARTILLERY CANNON BATTERY”:

The gun assembly provides instant identification of required deflection to the gunner or elevation to the assistant gunner. The display window shows quadrant elevation or deflection information. The tenths digit shows on the QE display only when the special instruction of GUNNER’S QUADRANT is received.

From this description we can surmise that the ID-2124 is used to display critical data to be used during the aiming and firing of the weapon. Further, the small size of the device and the use of binding posts seem to indicate that it would be used remotely or temporarily. Perhaps so the crew can put some distance between themselves and the artillery piece they’re controlling.

Now that we have an idea of what the ID-2124 is and how it would be used, let’s take a closer look at what’s going on inside that olive drab aluminum enclosure.

Continue reading “Milspec Teardown: ID-2124 Howitzer Data Display”