Not too long ago, part of using a computer was often finding the correct disk for the application you wanted to run and inserting it into your machine before you could start. With modern storage, this is largely a thing of the past. However, longing for some of that nostalgia, [ItsDanik] has been developing the RFIDisk, a 3D printed floppy drive that can kick off applications when their disk is inserted.

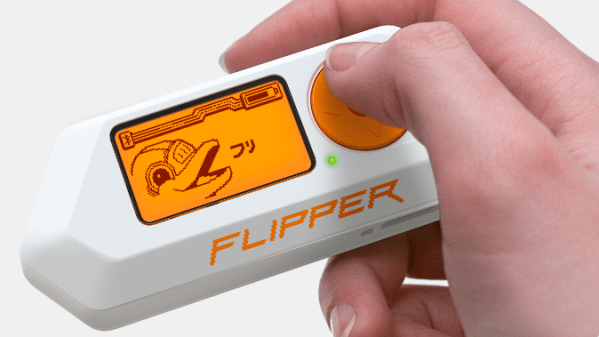

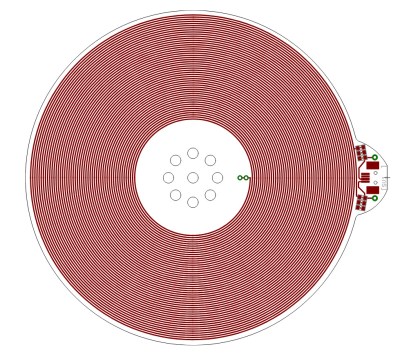

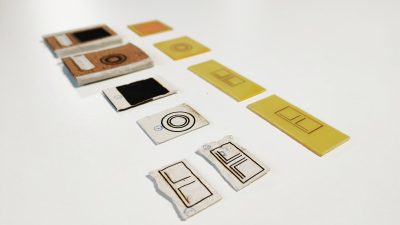

The desktop enclosure is printed to look like a standalone floppy drive, allowing use with either desktops or laptops. There’s the familiar 3.5 inch slot ready for your floppy disk, and there’s also a 1.3 in. OLED display on the front giving you feedback on the status of the RFIDisk — including telling you what’s currently inserted. Inside the enclosure is an Arduino Uno and an MFRC522 RFID reader. As the name would suggest, the way the RFIDisk enclosure reads its media is via NFC, not the traditional magnetic reader. Due to being RFID-based, the disks printed for the RFIDisk are solid without moving parts, but enclose a 25 mm NTAG213 NFC tag.

On the software side, [ItsDanik] has developed the RFIDisk Manager Python application, which is used to tie specific NFC tag IDs to commands to run when that tag is read. The application includes some nice features, such as being able to adjust the commands for both when the disk is first read and when it’s removed from the RFIDisk. You can also change what shows up on the OLED screen when the cartridge is inserted.

Using NFC to simulate physical media is a clever trick we’ve seen before, but if you’re looking for something with a bit more physical engagement, you could always put your USB devices into 3D printed cartridges.