We see a lot of clocks here at Hackaday, so many now that it’s hard to surprise us. After all, there are only so many ways to divide the day into intervals, as well as a finite supply of geeky and quirky ways to display the results, right?

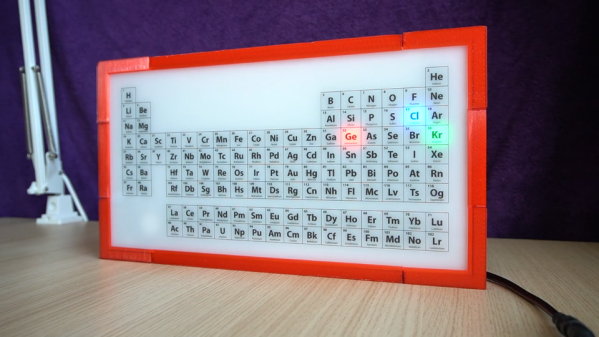

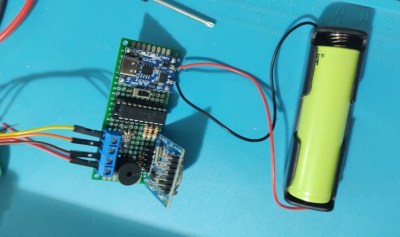

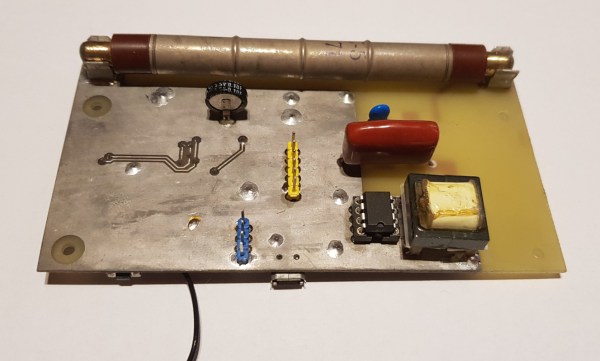

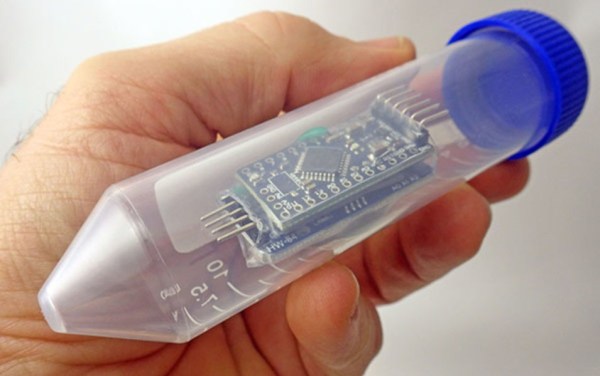

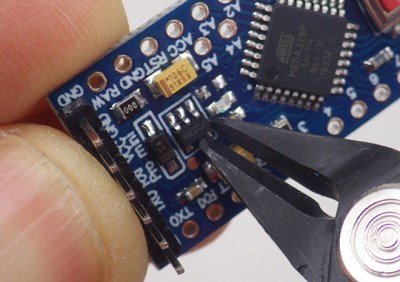

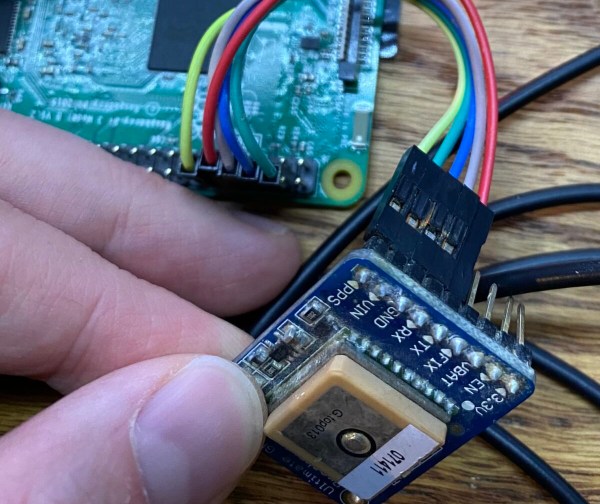

That’s why this periodic table clock really caught our eye. [gocivici]’s idea is a simple one: light up three different elements with three different colors for hours, minutes, and seconds, and read off the time using the atomic number of the elements. So, if it’s 13:03:23, that would light up aluminum in blue, lithium in green, and vanadium in red. The periodic table was designed in Adobe Illustrator and UV printed on a sheet of translucent plastic by an advertising company that specializes in such things, but we’d imagine other methods could be used. The display is backed by light guides and a baseplate to hold the WS2812D addressable LEDs, and a DS1307 RTC module gives the Arduino Nano a sense of time. The 3D printed frame of the clock has buttons for setting the time and controlling the clock; the brief video below shows it going through its paces.

We really like the attention to detail [gocivici] showed here; that UV printing really gave some great results. And what’s not to like about the geekiness of this clock? Sure, it may not be as action-packed as a game of periodic table Battleship, but it would make a great conversation starter.

Continue reading “Displaying The Time Is Elemental With This Periodic Table Clock”