Anyone who shops for robotics kits would have come across a few designed by Lynxmotion. They’ve been helping people build robots since 1995, from robot arm kits to hexapod chassis and everything in between. We would expect these people know their motors, so when they launched their own line of servo motors called Lynxmotion Smart Servos (LSS), it is worth spending a bit of time to look over what they offer.

While these new devices have a PWM mode compatible with classic remote control servos, unleashing their full power requires bidirectional communication over a serial bus. We’ve previously given an overview of three serial bus servos already on the market for comparison. A quick look at the $68-$100 price tags listed on Lynxmotion’s parent company RobotShop made it clear they do not intend to compete on price, so what interesting features do these new kids on the block have?

Digging into product documentation found some great details. Acceleration and deceleration rates are adjustable, which can help with smoother robot movement. There’s also an adjustable level of “stiffness” that adds some “give” (compliance) so a robot won’t have to be as stiff as… well, a robot!

Mechanically, the most interesting internal component is the magnetic position sensor. They are far more precise than potentiometers, but more importantly, they allow positioning anywhere within full 360 degrees. Many other serial bus servos are constrained to positions within an arc less than 360 degrees leaving a blind spot.

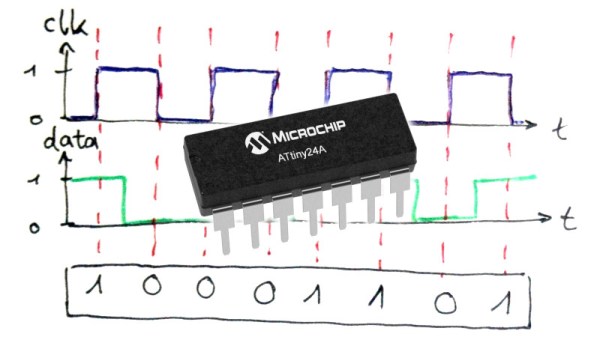

An interesting quirk of the LSS offerings is that the serial communication protocol uses human-readable text characters, so sending a number 255 means transmitting a three byte string ‘2’, ‘5’, and ‘5’ instead of single byte 0xFF. This would make debugging our custom robot code far easier, at the cost of reduced bandwidth efficiency and loss of checksum for detecting communication errors. It’s a trade-off that some robot builders would be happy to make, but others might not.

Externally, these servos have bountiful mounting options including some we didn’t know to ask for. Historically Lynxmotion kits have used a wide variety of servo mounting brackets, so they are motivated to make mechanical integration easy. The most novel offering is the ability to bolt external gears to the servo body. A set of 1:3 gears allow for gearing the servo up or down, or you can use a set of 1:1 gears for a compact gripper.

As you’d expect of servos in this price range, they all have metal gears, but they also have the ability to power the motor directly from a battery pack (a 3 cell lithium polymer is recommended). There are additional features, like an RGB LED for visual feedback, which we didn’t cover here so dig into the documentation for more. We look forward to seeing how these interesting little actuators perform in future robotics projects.