Robotic pets are sci-fi material, and [Kevin McAleer] from [Kev’s Robots] is moving us all ever so closer towards a brighter, happier, more robotic future. One of his latest robot builds, PicoCat, is a robot cat with servo-driven paws. It follows in the footsteps of the OpenCat project made by Dr. Rongzhong Li back in 2016, and we’re always happy seeing someone pick up where another hacker left off. [Kevin] took heavy inspiration from the OpenCat design – rebuilding it with hardware more friendly and accessible for makers today.

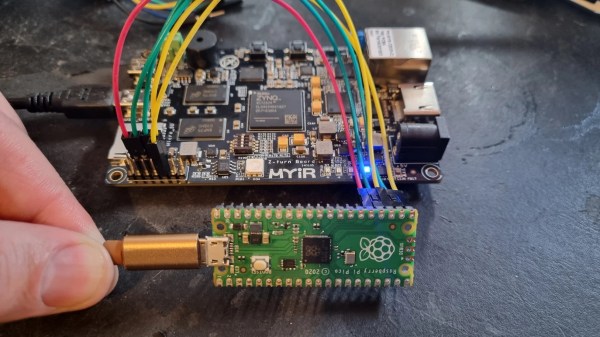

Projects like these, involving data processing and calculations to get the servos moving just right, stand to benefit from the computing power of recently released RP2040 MCU. As such, the Pimoroni Servo 2040 board is a crucial component of this build, being both the brains of the project and also a PIO-boosted driver for the eleven servos helping this robot come alive. This cat’s eyes are an ultrasonic sensor, and you can add a whole lot more sensors for any robotic intention of yours. Don’t expect this kitty to jump one meter high or scratch your favourite couch to death just yet, but there’s already a lot of potential, especially coupled with a small speaker.

Does this robotic cat interest you, whether it’d be due to your sci-fi propensity or a cat hair allergy? You’re in luck, because [Kevin] is keeping things firmly in the “open-source everything” realm. MicroPython code is stored in a GitHub repo, STLs are in a

Does this robotic cat interest you, whether it’d be due to your sci-fi propensity or a cat hair allergy? You’re in luck, because [Kevin] is keeping things firmly in the “open-source everything” realm. MicroPython code is stored in a GitHub repo, STLs are in a .zip linked on the page, and there’s plenty of renders to never leave you confused on what goes where. With all these resources, you can source the servos and the boards, fire up your 3D printer and sit down to assemble your own PicoCat. But not just that, [Kevin] also recorded three whole streams with insights, giving us over four hours of how-it-came-to-be video material for us to learn from. First, two streams of him designing the PicoCat in Fusion360, and then, him talking about the way he creates unit tests in MicroPython to improve his robots’ reliability and significantly reduce the amount of bugs cropping up.

This is not the last we will hear from [Kevin]’s robot-filled workshop, and previously, we’ve covered his Cray-1-shaped Pi Zero cluster system and a Raspberry Pi theremin, both as open and reproducible as this kitty! As you assemble yourself a PicoCat, or perhaps a Stanford Pupper or any of the other lovely quadru-pets we’ve previously featured, you might wonder how to properly move the servos, and we’ve covered a project that teaches you specifically that.

Continue reading “Build Your Own Cat – Some Assembly Required”