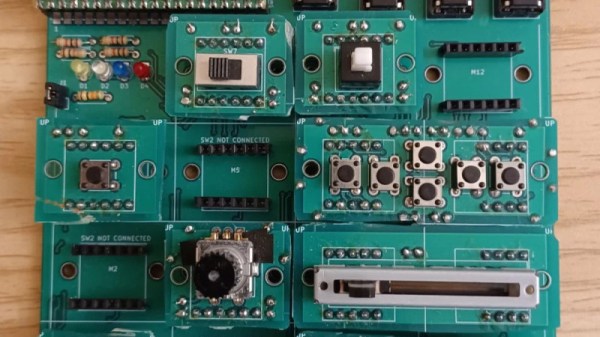

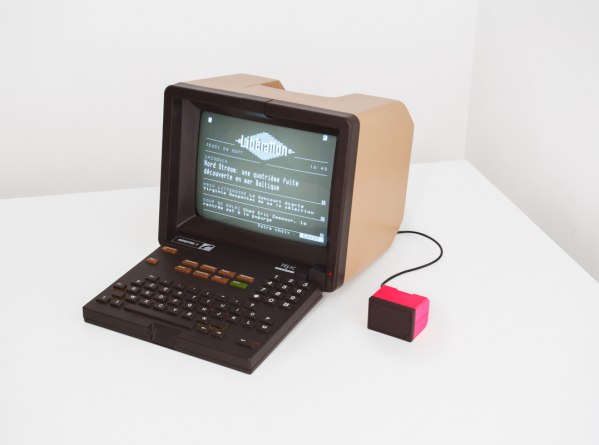

Over the past decade or so, amateur radio operators have benefited from an influx of inexpensive radios based around a much simpler design than what was typically commercially available, bringing the price of handheld dual-band or GMRS radios to around $20. This makes the hobby much more accessible, but they have generated some controversy as they tend to not perform as well and can generate spurious emissions and other RF interference that a higher quality radio might not create. But one major benefit besides cost is that they’re great for tinkering around, as their simplified design is excellent for modifying. This experimental firmware upgrade changes a lot about this Quansheng model.

With the obligatory warning out of the way that modifying a radio may violate various laws or regulations of some localities, it looks like this modified firmware really expands the capabilities of the radio. The chip that is the basis of the radio, the BK4819, has a frequency range of 18-660 MHz and 840-1300 MHz but not all of these frequencies will be allowed with a standard firmware in order to comply with various regulations. However, there’s typically no technical reason that a radio can’t operate on any arbitrary frequency within this range, so opening up the firmware can add a lot of functionality to a radio that might not otherwise be capable.

Some of the other capabilities this modified firmware opens up is the ability to receive in various other modes, such as FM and AM within the range of allowable frequencies. To take a more deep dive on what this firmware allows be sure to check out the original GitHub project page as well, and if you’re curious as to why these inexpensive radios often run afoul of radio purists and regulators alike, take a look at some of the problems others have had in Europe.