Most modern equipment is connected over USB, and generally speaking we’re all the better for it. But that’s not to say there aren’t some advantages to using serial and parallel ports. For example, the slower and less complex protocols can be a bit easier to debug when devices aren’t communicating, which [Jeremy Cook] demonstrates in his latest project.

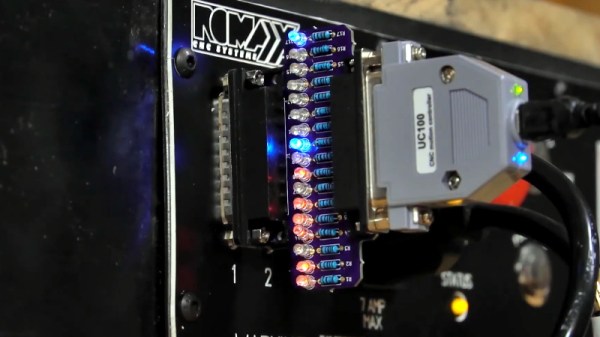

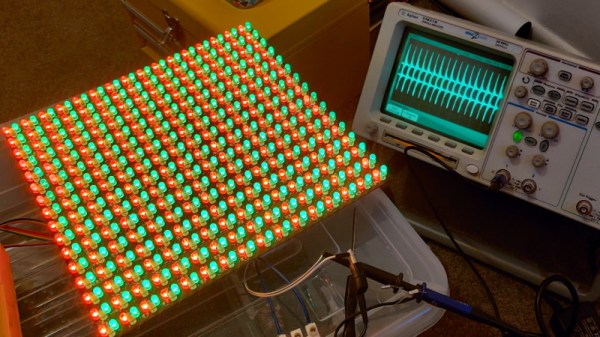

Looking to troubleshoot some communications problems he was having between his computer and CNC router, [Jeremy] came up with a handy little gadget that will allow him to visualize data passing through each pin of the parallel port in real-time. Even from across the room he can tell at a glance if communication is active, and with a keen eye, determine if he’s getting bi-directional traffic or not.

Looking to troubleshoot some communications problems he was having between his computer and CNC router, [Jeremy] came up with a handy little gadget that will allow him to visualize data passing through each pin of the parallel port in real-time. Even from across the room he can tell at a glance if communication is active, and with a keen eye, determine if he’s getting bi-directional traffic or not.

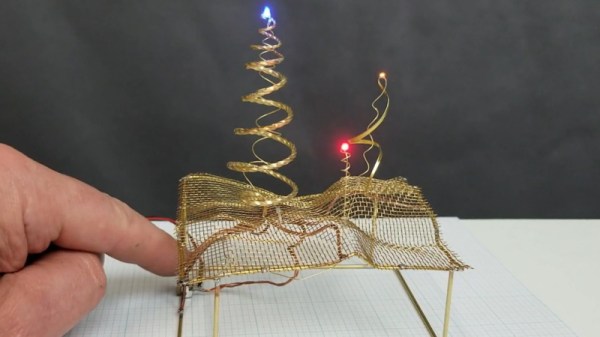

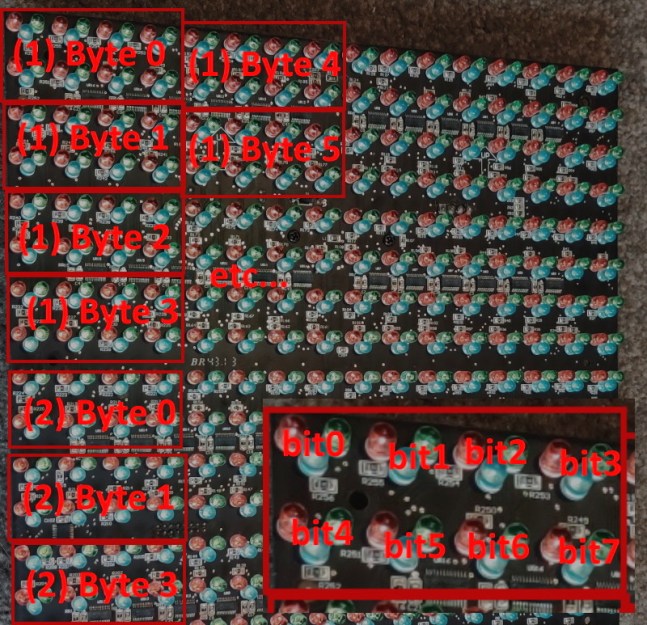

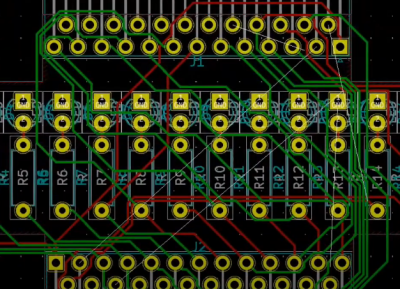

From a technical standpoint, this is a pretty simple project. The custom PCB is essentially just a pass-through, with an array of 3 mm LEDs and matching 10K resistors hanging off the data lines. But [Jeremy] found it to be an excellent excuse to brush up his KiCad skills. As he explains in the video after the break, this project certainly won’t impress the folks that do PCB design on a daily basis; but if you’re still learning the ropes, these are precisely the kind of projects you should be looking for.

Before any of you say it in the comments, we already know devices like this are available commercially for a few bucks. But that’s hardly the point. Things would be awfully slow around these parts if we disregarded any project that had a commercial alternative.