RISC-V is the new hotness, and companies are churning out code and announcements, but little actual hardware. Eventually, we’re going to get to the point where RISC-V microcontrollers and SoCs cost just a few bucks. This day might be here, with Seeed’s Sipeed MAix modules. it’s a RISC-V chip you can buy right now, the bare module costs eight US dollars, there are several modules, and it has ‘AI’.

Those of you following the developments in the RISC-V world may say this chip looks familiar. You’re right; last October, a seller on Taobao opened up preorders for the Sipeed M1 K210 chip, a chip with neural networks. Cool, we can ignore some buzzwords if it means new chips. Seeed has been busy these last few months, and they’re now selling modules, dev boards, and peripherals that include a camera, mic array, and displays. It’s here now, and you can buy one. If it seems a little weird for Seeed Studios to get their hands on this, remember: the ESP8266 just showed up on their web site one day a few years ago. Look where we are with that now.

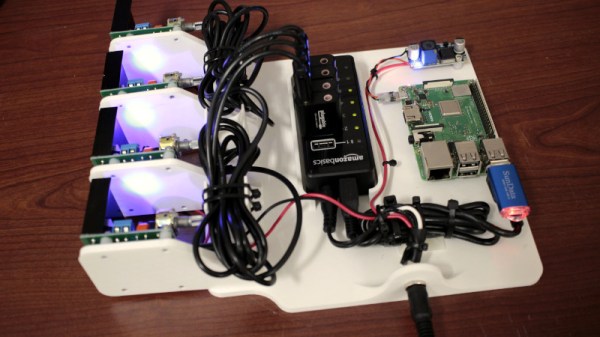

The big deal here is the Sipeed MAix-I module with WiFi, sold out because it costs nine bucks. Inside this module is a Kendryte K210 RISC-V CPU with 8MB of on-chip SRAM and a 400MHz clock. This chip is also loaded up with a Neural Network Processor, an Audio Processor with support for eight microphones, and a ‘Field Programmable IO array’, which sounds like it’s a crossbar on the 48 GPIOs on the chip. Details and documentation are obviously lacking.

In addition to a chip that’s currently out of stock, we also have the same chip as above, without WiFi, for a dollar less. It’ll probably be out of stock by the time you read this. There’s a ‘Go Suit’ that puts one of these chips in an enclosure with a camera and display, and there’s a microphone array add-on. There’s a binocular camera module if you want to play around with depth sensing.

The first time we heard of this chip, it was just a preorder on Taobao. It told us two things: RISC-V chips are coming sooner than we expected, and you can do preorders on Taobao. Seeed has a history of bringing interesting chips to the wider world, and if you want a RISC-V chip right now, here you go. Just be sure to tell us what you did with it.