When it was released, the Beckman Model 421 CRT controller represented the latest and greatest in liquid chromatography technology. Its 12 inch screen would allow the operator to view critical information such as flow rate and concentration, and its integrated keyboard simplified system control. It made liquid chromatography faster and easier, allowing lab technicians to focus on analysis rather than the complexities of operating the equipment.

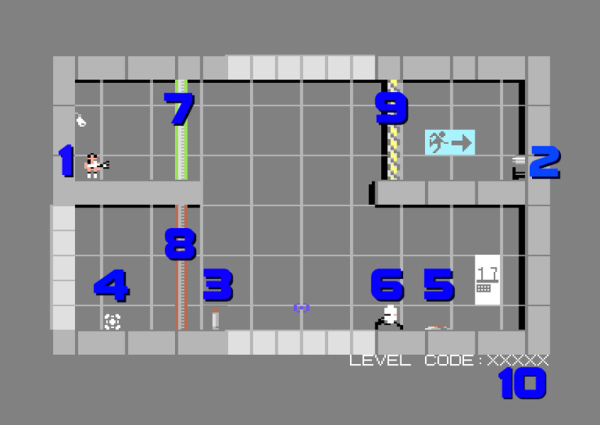

But none of that matters right now. What matters is that [Igor Afanasyev] found one of these gloriously vintage devices at a local swap meet and decided it deserved a second chance at life. With a Raspberry Pi and a surprising amount of support hardware, he was able to turn this roughly 40 year old piece of scientific equipment into a multipurpose device that does everything from classic gaming to multimedia playback. It’s got a few quirks, but overall this is a gadget that any hacker would love to have kicking around their modern-day lab.

But none of that matters right now. What matters is that [Igor Afanasyev] found one of these gloriously vintage devices at a local swap meet and decided it deserved a second chance at life. With a Raspberry Pi and a surprising amount of support hardware, he was able to turn this roughly 40 year old piece of scientific equipment into a multipurpose device that does everything from classic gaming to multimedia playback. It’s got a few quirks, but overall this is a gadget that any hacker would love to have kicking around their modern-day lab.

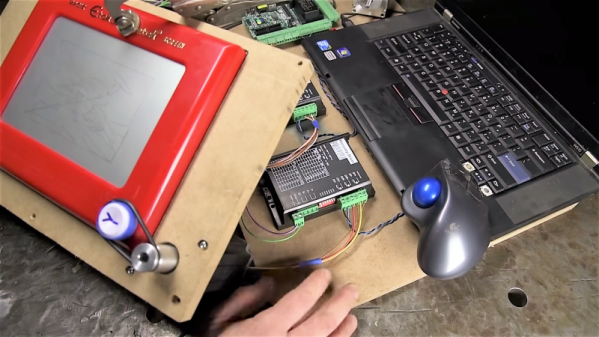

[Igor] explains that the Model 412 is essentially just a dumb terminal with no internal logic, so in theory it should have been possible to just hang the thing on a serial port and be done with it. But unfortunately the display drive board was dead, so a full rebuild was in order. This meant that there’s little left of the original device other than the keyboard and the case itself, but since it isn’t exactly a “vintage computer” in the traditional sense, we think the purists will allow it.

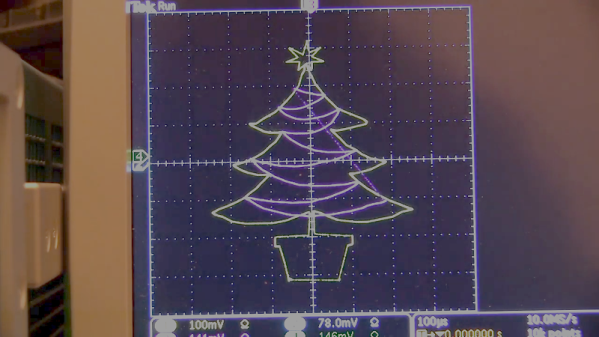

For the display, [Igor] used an LCD he salvaged from an old digital picture frame. It was the right size to fit the opening, and thanks to an unpopulated VGA header on the board, wasn’t too difficult to get connected to the Pi with an HDMI adapter. He also added a hardware VGA scanline generator board so that no matter what the Pi shows it will have that classic old-school look; a fantastic detail we don’t usually see on builds like this.

The keyboard on the Model 412 was more of a control panel than a traditional input device, so not only does it have keycaps which say things like “FLOW RATE” and “WRITE TAPE”, but it has a fairly weird layout. After reverse engineering the somewhat unusual key matrix, he spun up a custom firmware for the Arduino Pro Micro using QMK which would let him use the board on the Pi as a standard USB input device. But rather than replace the keys, [Igor] created a little cheat-sheet overlay that he could put over the board to see what keys translate to which letters. It’s awkward for sure, but we really appreciate that he preserved the unique nature and look of the Model 412.

Like the Heathkit H19 that was brought back to life with an internal Raspberry Pi or the DEC VT100 with a BealeBone inside there’s something about the visual aesthetic and no-nonsense approach of these vintage terminals which continue to make them compelling into the 21st century.