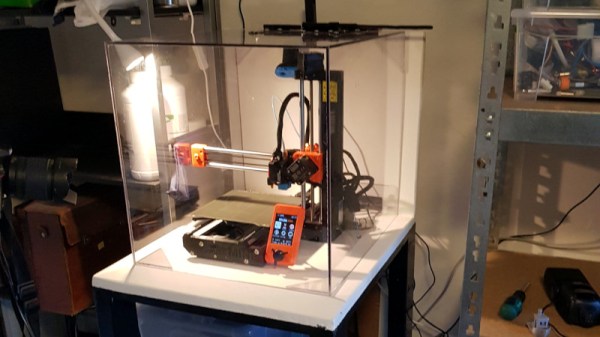

Even a decade later, homebrew 3D printing still doesn’t stop when it comes to mechanical improvements. These last few months have been especially kind to lightweight direct-drive extruders, and [lorinczroby’s] Orbiter Extruder might just set a paradigm for a new kind of direct drive extruder that’s especially lightweight.

Weighing in at a mere 140 grams, this setup features a 7.5:1 gear reduction that’s capable of pushing filament at speeds up to 200 mm/sec. What’s more, the gear reduction style and Nema 14 motor end up giving it an overall package size that’s smaller than any Nema 17 based extruder. And the resulting prints on the project’s Thingiverse page are clean enough to speak for themselves. Finally, the project is released as open source under a Creative Commons Non-Commercial Share-Alike license for all that (license-respecting!) mischief you’d like to add to it.

This little extruder has only been around since March, but it seems to be getting a good amount of love from a few 3D printer communities. The Voron community has recently reimagined it as the Galileo. Meanwhile, folks with E3D Toolchangers have been also experimenting with an independent Orbiter-based tool head. And the Annex-Engineering crew has just finished a few new extruder designs like the Sherpa and Sherpa-Mini, successors to the Ascender, all of which derive from a Nema 14 motor like the one in the Orbiter. Admittedly, with some similarity between the Annex and Orbiter designs, it’s hard to say who inspired who. Nevertheless, the result may be that we’re getting an early peek into what modern extruders are starting to shape into: smaller steppers and more compact gear reduction for an overall lighter package.

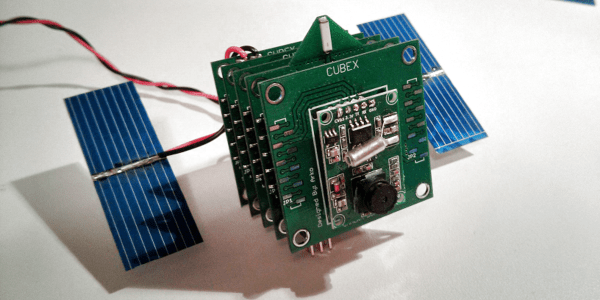

Possibly just as interesting as the design itself is [lorinczroby’s] means of sharing it. The license terms are such you can faithfully replicate the design for yourself, provided that you don’t profit off of it, as well as remix it, provided that you share your remix with the same license. But [lorinczroby] also negotiated an agreement with the AliExpress vendor Blurolls Store where Blurolls sells manufactured versions of the design with some proceeds going back to [lorinczroby].

This is a clever way of sharing a nifty piece of open source hardware. With this sharing model, users don’t need to fuss with fabricating mechanically complex parts themselves; they can just buy them. And buying them acts as a tip to the designer for their hard design work. On top of that, the design is still open, subject to remixing as long as remixers respect the license terms. In a world where mechanical designers in industry might worry about having their IP cloned, this sharing model is a nice alternative way for others to both consume and build off of the original designer’s work while sending a tip back their way.

Continue reading “A Featherweight Direct Drive Extruder In A Class Of Its Own” →