[Keith Decent] recently got himself involved in a plywood challenge, and decided to make a single-pickup electric guitar. Since he is a prolific hoarder of scrap wood, the result is a lovely stack of laminates from many sources, including reclaimed cabinet doors. Really though, the wood is just the beginning—nearly every piece of this texture-rich axe started life as something else.

He’s made a cigar box guitar before, but never a bona fide solid-body electric. As you might guess, he learned quite a bit in the process. [Keith] opted for a neck-through design instead of bolting one on and using a truss rod. The face pieces are cut from his old bench top, which has a unique topology thanks to several years of paint, glue, and other character-building ingredients.

We love the geometric inlay [Keith] made for the pick guard, and the fact that he used an offcut from the process as a floating bridge. He also made his own pickup from bolts, an old folding rule, and reclaimed magnet wire from discarded wall wart transformers. Once he routed out the body and installed the electronics, [Keith] cut up an old painting he’d done on plywood to use as the back panel. Our only complaint about this beautiful guitar is that he didn’t design the back piece to be dinosaur side out. Shred past the break to give her a listen.

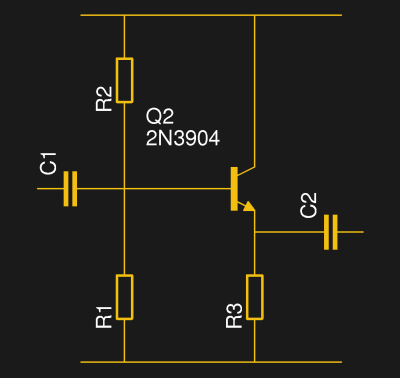

[Keith] wound his pickup with a little help from a drill, but a DIY pickup winder might have caused him less grief.