We’ve featured a great many unique clocks here on Hackaday, which have utilized nearly every imaginable way of conveying the current time. But of all these marvelous timepieces, the Morse code clock has the distinct honor of simultaneously being the easiest to construct and (arguably) the most difficult to read. As such, it’s little surprise we don’t see them very often. Which makes this latest entry into the field all the more interesting.

[WhisleyTangoHotel] has taken the basic concept of the Morse clock, which at its most simplistic could be done with a microcontroller and single LED, and expanded it into a (relatively) practical device. With both audio and visual signaling, and support for pulling the time from NTP, this is easily the most polished Morse code clock we’ve ever seen. Using it still requires you to have a decent grasp on Samuel Morse’s now nearly 200 year old encoding scheme of course, but on the bright side, this clock is sure to help keep your CW skills sharp.

[WhisleyTangoHotel] has taken the basic concept of the Morse clock, which at its most simplistic could be done with a microcontroller and single LED, and expanded it into a (relatively) practical device. With both audio and visual signaling, and support for pulling the time from NTP, this is easily the most polished Morse code clock we’ve ever seen. Using it still requires you to have a decent grasp on Samuel Morse’s now nearly 200 year old encoding scheme of course, but on the bright side, this clock is sure to help keep your CW skills sharp.

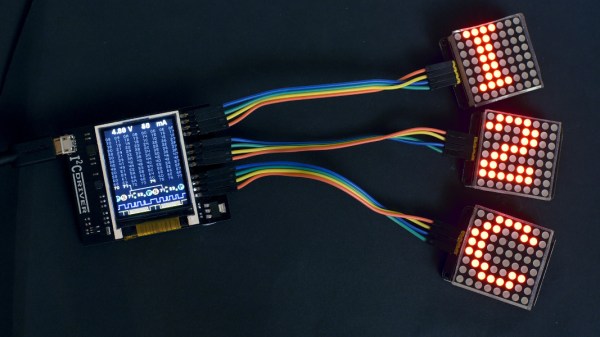

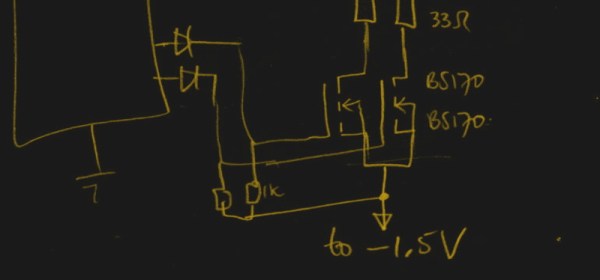

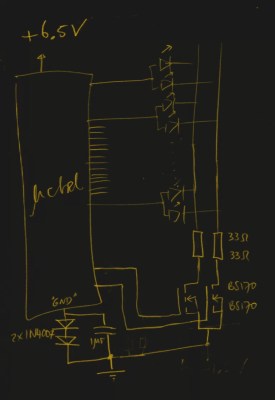

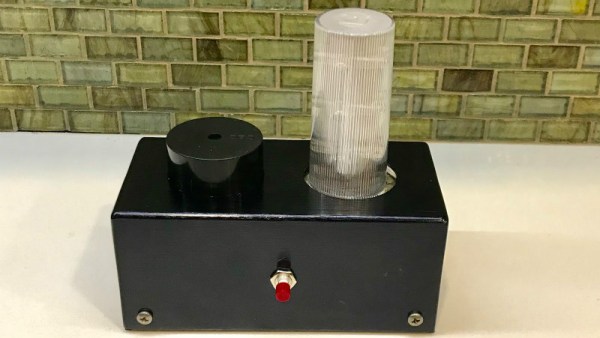

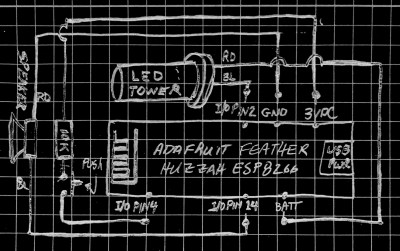

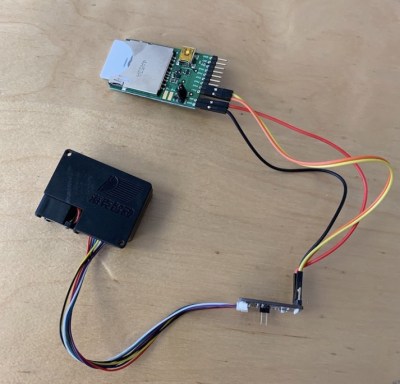

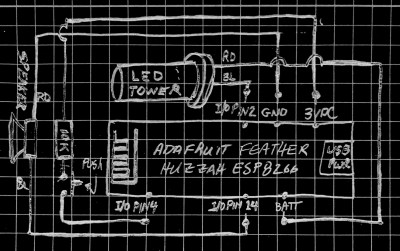

For those following along at home, [WhisleyTangoHotel] provides a hand-drawn diagram to show how everything connects together in his Morse timepiece, but there’s nothing on the hardware side that’s likely to surprise the Hackaday reader. A single momentary push button represents the device’s sole user input, with the output being handled by a LED “tower” and speaker on their own respective pins on the microcontroller. Here a Adafruit Feather HUZZAH is used, but any ESP8266 would work in its place.

Of course, the advantage of using an ESP8266 board over your garden variety MCU is the Wi-Fi connectivity. This allows the clock to connect to an NTP server and get the current time before relaying it to the user. Some might think this overkill, but it’s really a critical feature; the lack of a proper RTC on the ESP means the clock would drift badly if not regularly synchronized. Assuming you’ve got a reliable Internet connection, this saves you the added cost and complexity of adding an external RTC.

[WhisleyTangoHotel] wraps up his blog post by providing his ESP8266 Arduino source code, which offers an interesting example in working not only with NTP and time zones on the ESP, but how to handle parsing strings and representing their principle characters in Morse code.

Interestingly enough, in the past we’ve seen a single LED clock that didn’t use Morse code to blink out the time, which might be a viable option as an alternate firmware for this device if you’re not in the Samuel Morse fan club.

Continue reading “NTP Morse Code Clock Powered By ESP8266” →