Love it or loathe it, the pharmaceutical industry is really good at protecting its intellectual property. Drug companies pour billions into discovering new drugs and bringing them to market, and they do whatever it takes to make sure they have exclusive positions to profit from their innovations for as long a possible. Patent applications are meticulously crafted to keep the competition at bay for as long as possible, which is why it often takes ages for cheaper generic versions of blockbuster medications to hit the market, to the chagrin of patients, insurers, and policymakers alike.

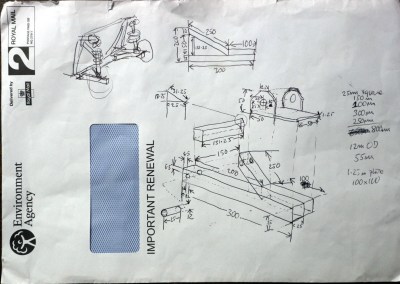

Drug companies now appear poised to benefit from the artificial intelligence revolution to solidify their patent positions even further. New computational methods are being employed to not only plan the synthesis of new drugs, but to also find alternative pathways to the same end product that might present a patent loophole. AI just might change the face of drug development in the near future, and not necessarily for the better.

Continue reading “AI Patent Trolls Now On The Job For Drug Companies”