Companies now are looking to secure revenue streams by sneakily locking customers into as many recurring services as possible. Subscription software, OS ecosystems, music streaming, and even food delivery companies all want to lock consumers in to these types of services. Battery-operated power tools are no different as there’s often a cycle of buying tools that fit one’s existing batteries, then buying replacement batteries, ad infinitum. As consumers we might prefer a more open standard but since this is not likely to happen any time soon, at least we can build our own tools that work with our power tool brand of choice like this battery-powered soldering station. Continue reading “Soldering Station Designed Around Batteries”

battery414 Articles

A Delicious Advancement In Battery Tech

Electronics have been sent to some pretty extreme environments, but inside a living host is a particularly tricky set of conditions, especially if you don’t want to damage the organism ingesting the equipment. One step in that direction could be an edible battery cell. (via Electrek)

Developed by scientists at the Istituto Italiano di Tecnologia, this new cell is made from food additives and ingredients to skirt any nasty side effects one might experience from ingesting a less palatable battery chemistry like NiCd. A riboflavin anode is coupled with a quercetin cathode, both with activated carbon to increase conductivity. Encapsulated in beeswax and with a separator made of nori algae, the battery is completely non-toxic.

The cell generates a modest 0.65V with a max sustained current of 48 µA for 12 min, but it shows promise as a power source for ingestible medical sensors, even if it won’t be powering your next mobile Raspberry Pi project. This isn’t the first time we’ve seen edible electronics; check out this screaming chocolate rabbit or robots made of candy.

Low-Power Wi-Fi Includes E-Paper Display

Designing devices that can operate in remote environments on battery power is often challenging, especially if the devices need to last a long time between charges or battery swaps. Thankfully there are some things available that make these tasks a little easier, such as e-ink or e-paper displays which only use power when making changes to the display. That doesn’t solve all of the challenges of low-power devices, but [Albertas] shows us a few other tricks with this development board.

The platform is designed around an e-paper display and is meant to be used in places where something like sensor data needs to not only be collected, but also displayed. It also uses the ESP32C3 microcontroller as a platform which is well-known for its low power capabilities, and additionally has an on-board temperature and humidity sensor. With Bluetooth included as well, the tiny device can connect to plenty of wireless networks while consuming a remarkably low 34 µA in standby.

With a platform like this that can use extremely low power when not taking measurements, a battery charge can last a surprisingly long time. And, since it is based on common components, adding even a slightly larger battery would not be too difficult and could greatly extend this capability as well. But, we have seen similar builds running on nothing more than a coin cell, so doing so might only be necessary in the most extreme of situations.

That Cheap USB Charger Could Be Costly

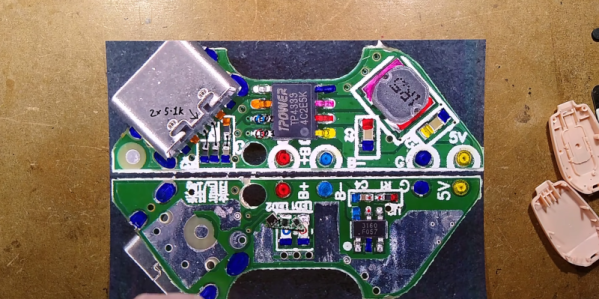

[Big Clive] picked up a keychain battery to charge his phone and found out that it was no bargain. Due to a wiring mistake, the unit was wired backward, delivering -5 V instead of 5 V. The good news is that it gave him an excuse to tear the thing open and see what was inside. You can see the video of the teardown below.

The PCB had the correct terminals marked G and 5 V, it’s just that the red wire for the USB connector was attached to G, and the black wire was connected to 5 V. Somewhat surprisingly, the overall circuit and PCB design was pretty good. It was simply a mistake in manufacturing and, of course, shows a complete lack of quality assurance testing.

The circuit was essentially right out of the data sheet, but it was faithfully reproduced. We should probably test anything like this before plugging it into a device, but we typically don’t. Does our phone protect against reverse polarity? Don’t know, and we don’t want to find out. [Clive] also noted that the battery capacity was overstated as well, but frankly, we’ve come to expect that with cheap gadgets like this.

This isn’t, of course, the first phone charger teardown we’ve seen. This probably isn’t as deadly as the USB killer, but we still wouldn’t want to risk it.

Morse Code Clock For Training Hams

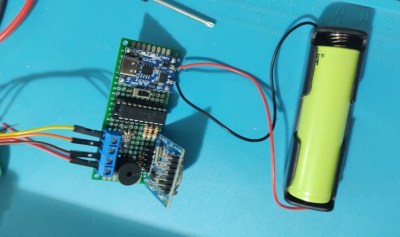

It might seem antiquated, but Morse code still has a number of advantages compared to other modes of communication, especially over radio waves. It’s low bandwidth compared to voice or even text, and can be discerned against background noise even at extremely low signal strengths. Not every regulatory agency requires amateur operators to learn Morse any more, but for those that do it can be a challenge, so [Cristiano Monteiro] built this clock to help get some practice.

The project is based around his favorite microcontroller, the PIC16F1827, and uses a DS1307 to keep track of time. A single RGB LED at the top of the project enclosure flashes the codes for hours in blue and minutes in red at the beginning of every minute, and in between flashes green for each second.

The project is based around his favorite microcontroller, the PIC16F1827, and uses a DS1307 to keep track of time. A single RGB LED at the top of the project enclosure flashes the codes for hours in blue and minutes in red at the beginning of every minute, and in between flashes green for each second.

Another design goal of this build was to have it operate with as little power as possible, so with a TP4056 control board, single lithium 18650 battery, and some code optimization, [Cristiano] believes he can get around 60 days of operation between charges.

For a project to help an aspiring radio operator learn Morse, a simple build like this can go a long way. For anyone else looking to build something similar we’d note that the DS1307 has a tendency to drift fairly quickly, and something like a DS3231 or even this similar Morse code clock which uses NTP would go a long way to keeping more accurate time.

Researchers Find “Inert” Components In Batteries Lead To Cell Self-Discharge

When it comes to portable power, lithium-ion batteries are where it’s at. Unsurprisingly, there’s a lot of work being done to better understand how to maximize battery life and usable capacity.

While engaged in such work, [Dr. Michael Metzger] and his colleagues at Dalhousie University opened up a number of lithium-ion cells that had been subjected to a variety of temperatures and found something surprising: the electrolytic solution within was a bright red when it was expected to be clear.

It turns out that PET — commonly used as an inert polymer in cell assembly — releases a molecule that leads to self-discharge of the cells when it breaks down, and this molecule was responsible for the color change. The molecule is called a redox shuttle, because it travels back and forth between the cathode and the anode. This is how an electrochemical cell works, but the problem is this happens all the time, even when the battery isn’t connected to anything, causing self-discharge.

Continue reading “Researchers Find “Inert” Components In Batteries Lead To Cell Self-Discharge”

Lithium Sulfur Battery Cycle Life Gets A Boost

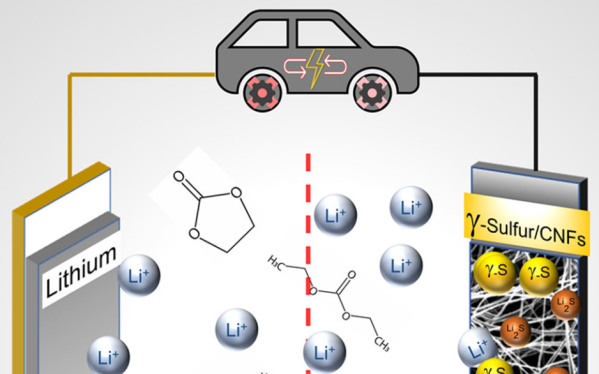

Lithium sulfur batteries are often touted as the next major chemistry for electric vehicle applications, if only their cycle life wasn’t so short. But that might be changing soon, as a group of researchers at Drexel University has developed a sulfur cathode capable of more than 4000 cycles.

Most research into the Li-S couple has used volatile ether electrolytes which severely limit the possible commercialization of the technology. The team at Drexel was able to use a carbonate electrolyte like those already well-explored for more traditional Li-ion cells by using a stabilized monoclinic γ-sulfur deposited on carbon nanofibers.

The process to create these cathodes appears less finicky than previous methods that required tight control of the porosity of the carbon host and also increases the amount of active material in the cathode by a significant margin. Analysis shows that this phase of sulfur avoids the formation of intermediate fouling polysulfides which accounts for it’s impressive cycle life. As the authors state, this is far from a commercial-ready system, but it is a major step toward the next generation of batteries.

We’ve covered the elements lithium and sulfur in depth before as well as an aluminum sulfur battery that could be big for grid storage.