The price of lithium batteries has plummeted in recent years as various manufacturers scale up production and other construction and process improvements are found. This is a good thing if you’re an EV manufacturer, but can be problematic if you’re managing something like a landfill and find that the price has fallen so low that rechargeable lithium batteries are showing up in the waste stream in single-use devices. Unlike alkaline batteries, these batteries can explode if not handled properly, meaning that steps to make sure they’re disposed of properly are much more important. [Becky] found these batteries in single-use disposable vape pens and so set about putting them to better use rather than simply throwing them away.

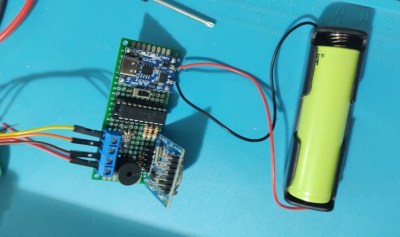

While she doesn’t use the devices herself, she was able to source a bunch of used ones locally from various buy-nothing groups. Disassembling the small vape pens is fairly straightforward, but care needed to be taken to avoid contacting some of the chemical residue inside of the devices. After cleaning the batteries, most of the rest of the device is discarded. The batteries are small but capable and made of various lithium chemistries, which means that most need support from a charging circuit before being used in any other projects. Some of the larger units do have charging circuitry, though, but often it’s little more than a few transistors which means that it might be best for peace-of-mind to deploy a trusted charging solution anyway.

While we have seen projects repurposing 18650 cells from various battery packs like power tools and older laptops, it’s not too far of a leap to find out that the same theory can be applied to these smaller cells. The only truly surprising thing is that these batteries are included in single-use devices at all, and perhaps also that there are few or no regulations limiting the sale of devices with lithium batteries that are clearly intended to be thrown away when they really should be getting recycled.

Continue reading “Harvesting Rechargeable Batteries From Single-Use Devices”